|

When McLean County entrepreneurs began developing their businesses in the 19th century, few of them thought about dealing with organized workers. Yet as quickly as industrialization spread, workers began to form organizations, seeking mechanisms to control the workplace and have a voice on the job.

Worker organizations can trace their roots to medieval guilds. But modern trade unions evolved in distinctly different ways, because the nature of work itself changed. Pre-industrial craft workers had power because they controlled their work. Apprenticeship and craft traditions put power into workers' hands. Although they might work for a master and survived an often cruel apprenticeship, once a worker attained the status of "journeyman" that worker could literally travel, insured of skill-based credentials. A master needed the skills and expertise of these workers and this gave the workers latitude at the workplace. Although craft workers might labor for ten hours or more, they controlled the pace of work and their output. There were no time clocks to punch and breaks and other relaxation were often chosen by the worker. "In many ways, the early manufacturing work rhythm was more similar to the labor patterns of agricultural society than to those of modern capitalism (Clawson, 39)."

The Illinois Legislature, one year after statehood in 1819, passed one of its first labor laws, regulating conditions for apprentices. The Apprenticeship Law provided that all male apprentices had to be discharged, that is, have completed their apprenticeship and not retained any longer at lower wages, by age 21 for males and 18 for females. If the apprentices were abused, mistreated or not given adequate food or clothing, they could be released earlier (Karno, 1).

Early McLean County registers a few of these craft guilds. In November 1853 Bloomington's "Boss Boot and Shoe Manufacturers" announced sale prices for various kinds of shoes and boots. The highest item, a hand-sewn pair of boots, was set at $7.50. The 11 shops represented by the organization used their organized power to set prices, in the tradition of the medieval guilds.. All agreed to charge the same rate for their customers (Intelligencer, 2).

Economic change was ending the older system of a slower workday and craft control. Larger enterprises, better transportation and increased demand brought pressure on the old rhythms of the workday.

"...Substantial changes in the productive process were also occurring. These crafts bore the stamp of an increasingly powerful merchant capitalist group. As improved canal and turnpike transportation opened new markets, the merchant capitalist bought raw materials, found a producer to manufacture them into finished goods, and secured buyers for their sale. The master craftsman who owned a workshop became little more than a labor contractor (Roediger & Foner, 8).

By the time McLean County was settled by Europeans, craft work was still viable, but a new process was re-arranging work processes. The factory system, first developed during England's late 18th century Industrial Revolution and then spread by American textile makers, was transforming work. The centralized machinery of an early textile mill ran off a water-powered system, with all the looms running simultaneously at the same speed. To operate productively, these new factories needed workers positioned throughout the factory to work the machines. The power system, not the worker, set the pace of production. And insuring this system operated properly required workers arriving and starting work simultaneously. A strict adherence to starting times and breaks was followed. Workers became "hands" in the factory system, adjuncts to the machinery, no longer controlling the pace or the timing of work. Early factory "hands" were primarily female or children and eventually immigrants, new participants in wage labor who did not control a craft or skill which they could leverage for more control (Hindle & Lubar, 196-199). Some scholars cite the factory system's logic as not only a technologically-driven development, but an attempt to control labor by centralizing production under one roof (Smith, 88-91).

Some would argue that it this transformation was not as much technically driven as it was spurred by capital's desire to control labor and its output. "...The creation of the factory meant that capitalists could decide the hours of labor. Workers were given the choice' of not working at all, or else working on the capitalist's terms, which required employees to work twelve or fourteen hours a day, six days a week (Clawson, 48)."

Craft work itself began to change; masters, who had traditionally labored alongside their journeymen, became more and more supervisors or contractors. The traditional bonds which united the two began to unravel and by colonial times journeymen were forming separate organizations from masters. Many were making a distinction between "capital," that is, those who lived by their investments, and "labor," which was not limited to the working class, but included anyone deemed "socially productive." This included small businesses and farmers. Noah Webster, in his dictionary, makes this distinction. And when Abraham Lincoln said that "Labor is the superior of capital," he did not mean labor as the working class, but labor as the productive class. This distinction made the early Republican Party the organization for "free men and free soil" -- anti-slavery, for homestead settlement, and promoting the interests of the "producers" in society.

By the 1830s craft unions were common in northeastern U.S. cities, negotiating wages and hours with employers and agitating, through their own newspapers, for political suffrage and free public education.

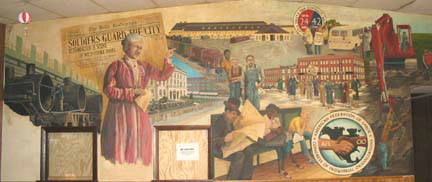

The other instrument which spread trade unionism, particularly in McLean County, was the railroad. Although the railroad promised increased trade and employment opportunities, it could be a cruel employer. Immigrant labor was recruited for the back-breaking spade, pick and hammer work of grading rail roadbeds and laying track. In Funk's Grove is a poignant reminder of this labor's toll. In the Funk-Stubblefield Cemetery, alongside the Union Pacific Railroad's tracks, are the unmarked graves of 55 immigrant workers, predominately Irish laborers. The circumstances of their death are not clear, but mass deaths from cholera or other epidemics in rail camps were not uncommon. The Alton and Sangamon Railroad was building from Springfield to Bloomington in 1853, and these workers could have been victims of railroad accidents or work camp epidemics. In the same period the Illinois Central Railroad was building north to south across the middle of Illinois, then the world's largest construction project. Over 100,000 names appear on the Illinois Central's payroll for the four years of construction, approximately 10,000 at any one time, mostly Irish and some German immigrants (Corliss, 52-59).

McLean County's first recorded strike and protest came in 1859, when the Alton and Sangamon, later the Chicago & Alton Railroad, had finally reached Chicago. The company was paying workers in script and had threatened pay cuts. The workers drew up a petition to the Governor, asking that their wages stay at the same rate. The petition, full of mainly Irish surnames, lists the employees at each section of the line.

Managing a large, geographically complex enterprise like a railroad was a new undertaking. A railroad required precision and coordination between unseen parties across distant miles. Railroads developed a rigorous, almost military management style, which became a model for 19th century corporate development.

Taming the iron horse was economic opportunity for workers as they became engineers, firemen or conductors. Or they adapted traditional craft skills in metal and wood working, like they did at Bloomington Chicago & Alton Railroad Shops repair shops, to the railroad's needs. They were all potential victims. The new technology was crude and accidents were common. Derailments, boiler explosions, link and pin couplers, inadequate braking systems and collisions all took their toll on railroader's lives and limbs. There was no workers' compensation law. If a workers was injured or killed on the job the survivors had to sue the company, and most courts ruled it was the worker's negligence, not the company's, that caused the accident.

Workers' first response, besides protest, was mutual protection. Printers, iron moulders and railroaders were amongst the first to form national unions. When the Brotherhood of the Footboard formed in 1863 to organize locomotive engineers, Bloomington workers were present, forming what became Lodge 19 of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. The organization's original purpose was not collective bargaining with their employer, but mutual protection. The Brotherhood protected the worker through an elaborate insurance system. Originally, if a worker was seriously injured or killed on the job, a national collection was taken of all members to support that worker or his widow. By 1908 BLE Lodge 19's 140 local members were paying $4 monthly in dues to their local organization, $2.50 to the national office, plus they had to carry at least $30 per year in BLE insurance. However, the worker who died or lost a limb or was otherwise incapacitated received support from the Brotherhood for life (Prince & Burnam, p. 887).

The BLE was followed by other railroaders in organizing. Briefly in 1865 a Machinists Association appeared amongst the Alton's shop workers, but it disappeared. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Fireman organized in 1876, the Order of Railway Conductors Local 87 in 1883 and the Brotherhood of Railway Trainmen in 1885.

In the non-railroad field local printers organized in 1869, surviving organizationally for about five years before re-emerging again as International Typographical Union 124 in 1884. The Iron Moulders of North America Local 157 established themselves in the local foundries by 1874. The Cigar Makers International Union followed in 1879 and the Journeymen Tailors Union in 1883 (Prince & Burnham, 889-890).

Although it was rarely enforced, Illinois workers had to be careful in organizing their new unions. In 1863 the Illinois legislature passed what was known as the "LaSalle Black Law," which imposed a $100 fine on anyone who used "threat, intimidation or otherwise seeks to prevent any other person from working." A "combination" of people to deprive some one the use of their property could be fined up to $500 (Staley, 8).

Although workers may not have had unions, that did not stop them from organizing or using national situations to their advantage. In 1877, during a national depression, railroad workers spontaneously struck across the country, burning the Pennsylvania Railroad's equipment in Pittsburgh, taking control of St. Louis and fighting armed battles in Chicago streets. C&A shop workers, although not striking, threatened to do so unless they received a wage increase.

|