|

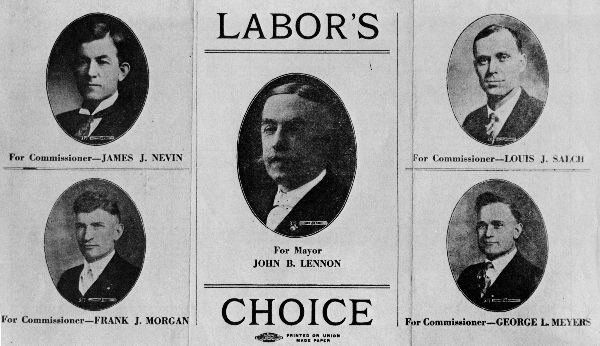

| This 1919 flier highlighted the Bloomington Labor Party candidates. |

|

Union involvement could mean better conditions for workers and a feeling of camaraderie and unity, especially when dealing with distant employers. It could also be an opportunity for individual advancement. A articulate or opportunistic individual working class member could gain social acceptance, power and prestige through union involvement. Two Irish-American Bloomington west-siders, born to railroad families in the rail shop's shadows, achieved national union leadership. Another national union leaders transferred himself from New York City to Bloomington, cementing connections to the national labor movement.

Patrick Morrissey, savior of the Railroad Trainmen

Patrick H. Morrissey, son of C&A section foreman John Morrissey and his wife Mary, was born September 11, 1862. For years the family lived at 803 W. Monroe Street in Bloomington. He completed a rare event for a 19th century working class child -- he graduated from Bloomington High School in 1879. Only 27 youngsters received degrees that year and only five of them were males. His classmate Lizzie Irons, later Mrs. Elizabeth Folsom, was the first female to win the O. Henry prize for fiction. Fred Haggard became a missionary to India and later secretary of the American Baptist Missionary Union. And Gordon M. Lillie was better known years later as "Pawnee Bill," traveling the nation with his wild west show.

Morrissey worked through his schooling as a "call boy," summoning railroaders from their homes when it was time for their run. After graduation he followed his dad to the railroad, working as a clerk, brakeman and conductor.

In 1883 trainmen on the Delaware & Hudson Railroad formed the Brotherhood of Railroad Brakeman, the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen after 1890. In 1885 Bloomington workers organized a lodge and Morrissey was a charter member. That year his fellow workers elected young Morrissey to represent them at the union's Burlington, Iowa convention. He caught the eye of S.E. Wilkinson, the new organization's Grand Master, and Morrissey became the BRT's clerk, editing the union's "Journal."

In 1889 Morrissey was elected Vice-Grand Master, traveling the country helping establish new lodges. The financial downturn of the 1890s and the Pullman strike defeat left the BRT penniless and dwindling. Wilkinson retired and in 1895 Morrissey was elected BRT Grand Master. The organization had less than 10,000 members and was $105,000 in debt.

Morrissey saved the organization, strategically uniting with the Order of Railway Conductors. Following the Pullman strike all the operating brotherhoods attempted cooperative efforts, but this fell apart within three years. In 1902 the Conductors and Trainmen confronted the western railroads together, successfully winning a contract which they replicated in other regions. The key strategic move the two organizations made was confronting railroads regionally, rather than individually, thus thwarting the companies' attempts to play workers on one line against another.

Although the railway brotherhoods tended to be conservative and often aloof from other unions, Samuel Gompers noted Morrissey as one of 20 "outstanding fellows" who answered his pleas for support for West Virginia coal miners in 1902.

When Morrissey left the BRT in 1909 it had 120,000 members, held $2 million in insurance funds and had a $1.5 million strike fund. The union also opened a home for disabled and aged trainmen in Highland Park, Illinois in 1910. He was noted for his education and as a public spokesman for the rail brotherhoods:

With a varied training in railroading, in insurance, and in labor organization work, Morrissey was in many ways the antithesis of his predecessors who had, in a powerful and brusque way, prepared the way for his analytical and judicious leadership. He was unusually well informed.... This knowledge, together with his forcefulness, tact, parliamentary ability, and rare good judgement, soon made him the spokesman of all the railway Brotherhoods in their joint conferences and their leader before the public (Orth, 158-159).

For the next five years Morrissey worked in Chicago for the American Association of Railway Employees and Investors, which invested union funds in rail companies. In 1914 he became a special assistant to the president of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad. Two years later he was diagnosed with a "nervous breakdown," which was actually a brain tumor. He died at age 54 on November 25, 1916 and is buried in Galesburg, Illinois.

Morrissey's brothers all were politically active in local affairs and moved beyond their working class background and the railroad. Brother Michael was elected Bloomington Police Magistrate, learned law, and served as a successful labor arbitrator and lawyer, becoming Bloomington postmaster during Democratic administrations. James Morrissey joined the Bloomington Fire Department, retiring as an assistant chief. John was on the Bloomington Election Commission. The one brother to leave town was William, who went to Denver, was active in the labor movement, wrote for the Denver Post and served on the Colorado Boxing Commission (Matejka).

Saving the Letter Carriers - Michael T. Finnan

Bloomington Letter Carriers Branch 522’s formal name is the “Michael T. Finnan NALC Branch 522.” Michael T. Finnan (1866-1942) was a National Association of Letter Carrier (NALC) officer. In Bloomington, Finnan’s delivered mail on postal route 1, which covered downtown. He joined the union’s national executive board in 1903, became assistant secretary in 1917, and from 1924-1941 served as the union’s national secretary. On assuming national office, one of his duties was editing the NALC’s publication, The Postal Record. He lobbied Congress during his leadership years; thanks to these efforts, the U.S. Postal Service officially recognized postal worker organizations, a civil service retirement act was passed and letter carriers’ work hours were reduced to 40 weekly. When the union was in a financial crunch, Finnan offered his life savings to keep the organization afloat. (Pantagraph May 26, 1942, page 6, Nov 2, 1908 page 2, Mikusko, M Brady, Carriers in a Common Cause: A History of the Letter Carriers & the NALC, NALC, Washington DC 2006)

IBEW's Depression and World War II leader - Daniel Tracy

Another west-side Bloomington Irish rail worker's son who achieved national leadership was Daniel W. Tracy, president of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. Morrissey was already working on the railroad when Tracy was born on April 7, 1886 at 1311 West Walnut Street in Bloomington, preceding by three sisters.

New electric technology provided Tracy's road to success, but it predominately came beyond Bloomington. After 1893 his father worked for the local street railway. Tracy completed grade school, worked briefly at the C&A shops and then began working for the street railways, occasionally listed as a laborer and later as an electrician.

Tracy last listed Bloomington as his address in 1913, migrating to the southwest. That year he joined IBEW Local 716 in Houston, working as a lineman in Texas and Oklahoma. Within three years he was business agent for two Houston locals and by 1920 was an International Vice-President for the union, representing the southwest. In 1933, with the union's membership at a record low because of the Depression, Tracy assumed the national organization's leadership, when there were 50,000 members.

By 1940, under Tracy's leadership and thanks to new legislation favorable to union organization, the IBEW had 200,000 members. A strong supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt, Tracy left the union in 1940 to serve as assistant Secretary of Labor under Frances Perkins. He returned to the union's presidency in 1947, served on the AFL's executive council, and led the IBEW as it grew to 360,000 members. He helped strengthen the union's apprenticeship programs and established a pension fund in 1946. A fierce anti-communist, Tracy's post-war reign was marked by tension with unions accused of being communist-led. He resigned his union presidency in 1954 and died in 1955. He's buried in Bloomington's St. Mary's Cemetery (Matejka).

The Presbyterian tee-totaler - John B. Lennon

Perhaps the most fascinating labor leader to impact Bloomington labor was John Brown Lennon of the Journeyman Tailors. Born in Lafayette County, Wisconsin on October 12, 1850, Lennon's family moved to Hannibal, Missouri within two years, where he learned the tailor's trade from his father. After some education, including seven months at Oberlin College in Ohio, Lennon moved to Denver, where he worked farming and mining before returning to the tailor's trade. He married June Allen in 1871 and they had one son.

Lennon also dates his union membership from that year. He quickly became active in Colorado activities, helping organize the city's central labor council and running for mayor on a labor-socialist ticket. In August 1884 the Journeyman Tailors Union (JTU) reorganized and Lennon represented the Denver tailors. The next year 23 local unions, representing 2,481 tailors, met in convention again. Lennon was elected vice-president.

In 1886 the JTU elected Lennon general secretary, responsible for the union's affairs and editor of "The Tailor." He relocated to New York, where half the union's membership lived. The union's income that first year was $300.

By 1907 the union had grown to 22,000 members in 400 local unions. Lennon also moved forward in the larger labor movement, becoming AFL treasurer in 1890. Gompers and Lennon became friends and in 1894 when the AFL president lost his post for one year to a socialist opponent, he operated from Lennon's office.

1894 almost destroyed the JTU after a disastrous New York strike. With the union's membership centered now in the Midwest, Lennon decided to relocate its national headquarters to Bloomington, setting up shop on January 1, 1896 in the Eddy Building, 427 N. Main Street. The family residence was at 614 East Mulberry Street.

Lennon quickly became active in local union affairs and helped lead the Trades & Labor Assembly, assisting and promoting local unions. Gompers came to Bloomington on June 23, 1899 to visit Lennon and addressed a labor rally that evening. Lennon took his AFL treasurer position seriously and warned the organization against over-expenditure. He also strongly supported Gompers' stances, drawing criticism from Gompers' opponents. In 1909 Lennon was the first president of the AFL's Union Label Department and helped form a Labor Press Association.

Gompers visit in 1896

“There has never been any achievement by man except it has been by organization. ... All branches of commerce are organized. Bankers and manufacturers, who control the millions, have organized. Why should not we, who have nothing to control but our labor, organize?”

Those were the words from Samuel Gompers (1850-1924), first President of the American Federation of Labor, speaking in Bloomington on May 18, 1896.

In the days before radio, television and the internet, public speeches were an effective way to hear new and diverse ideas. Gompers appeared at Bloomington’s Grand Opera House on May 18, 1896.

A parade was planed to welcome the AFL leader, but heavy rains canceled the street demonstration.

Why Bloomington? One of Gompers’ closest associates, John B. Lennon (1850-1923) of the National Tailors’ Union, had recently moved the union headquarters from New York City to Bloomington five months earlier. A disastrous New York strike forced the union to centralize in the Midwest, where more members remained.

Gompers was a Jewish immigrant from London, becoming an apprentice cigar maker at age ten. At 14 he joined the Cigarmakers Union and at age 25, became his local union’s president.

In 1881, he helped found what became the AFL. When the group re-organized in 1886, he became the organization’s President, an office he held until his death, except for 1895, when a Socialist faction won the labor presidency.

Although the AFL became the nation’s leading labor federation, it was one of many voices clamoring for change, including the Knights of Labor, various Socialist political factions and local union movement. Under Gompers’ leadership, by 1904 the AFL could claim four million members.

Gompers originally supported Socialist ideas of common property ownership, but eventually centered his philosophy on workers gaining power through organizing together, less on political change.

He and Lennon were especially close, both the same age. When Gompers lost the AFL presidency in 1895, Lennon let Gompers use his office as he sought to regain the presidency.

The Pantagraph described Gompers as “short in stature, heavy-built, with a dark complexion and expressive features.”

While in Bloomington, Gompers spoke about child labor, the eight-hour day and machines replacing workers.

At the time, 12 to 14-hour workdays were common, six days per week. Gompers proclaimed that workers needed to work to live, not live to work.

“We hold what is advocated by many, eight hours for work, eight hours for rest and eight hours for recreation. ... The man who works too many hours has no opportunity to cultivate better homes.

“We want more time: time, which is the great essence and end of our lives, which begins with our being and ends with our death, the great factor in production, the determiner of all value, time to live the lives of better men, time to cultivate ourselves, leisure to live, leisure to love and leisure to taste our freedom.”

Child labor was a potent issues, declared illegal in some states, but there was no national law. Illinois would pass its first child labor law in 1903, the federal law would not come until 1938.

Addressing child labor, Gompers said,

“Children of six or seven years of age are working in the mines and in the mills,

producing wealth, grinding their very bones into dollars. My heart goes out in sympathy to men and women, yet they can protect themselves if they will, but more so to the children taken from the school and from the play ground and put to labor in our mills and factories. Their wrongs are an indictment of our civilization.”

Gompers concluded by challenging the crowd: “Men of Bloomington, be and doing! We have the choice of having this grand republic of ours overthrown or to come under the banner of organized labor. We must win!” (Pantagraph, 7, Bulletin, 2, May 19, 1896)

Lennon lost power in 1910 when he was defeated as JTU general secretary by Eugene Brais, a Canadian socialist. Brais publicly advocated socialism, but another pressing issue of the early 20th-century might account for Lennon's defeat -- alcohol. Unlike many trade unionist, who often met and organized in neighborhood taverns, Lennon was a strict prohibitionist and temperance advocate. In a national union movement dominated by Irish Catholic surnames, Lennon was a traditional White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, active in the Masons. He wrote strident articles for national Protestant and temperance magazines, condemning strong drink.

Although no longer a national union officer, Gompers insisted on retaining Lennon as AFL treasurer, referring to him as "my minister without portfolio." In 1912 Congress established an industrial relations study to hold national hearings. Gompers appointed, to the protest of progressive groups, Lennon as his personal representative.

In 1917 Daniel Tobin of the Teamsters replaced Lennon as AFL treasurer. Although he had taken an anti-war stance in 1916, Lennon was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to the new U.S. Department of Labor's board of mediators, a position he served on through the war years.

In 1919, when Lennon was one year short of 70, his wife died. Lennon quickly remarried Barbara Eggers, a Bloomington school teacher with whom he had developed a friendship after her graduation from Bloomington High School in 1900.

1919 was also a politically auspicious year for Lennon. He took a stance Gompers frowned on, actively participating in forming an Illinois Labor Party.

Inspired by the post-World War I reconstruction plan of the British Labour Party, the Illinois State Federation of Labor met in convention in Bloomington in November 1918, adopting "Labor's Fourteen Points" as a political platform. The convention debated and supported the idea of a Labor Party. The 14 Points included the right to organize unions, democratic control of industry, establishment of a minimum wage and an eight-hour day, inheritance taxes and "an end to kings and wars." A statewide poll of union members overwhelmingly supported establishing a labor party by a ten-to-one margin (Staley, 363-364).

A convention was called for Springfield, Illinois on April, 10, 1919 to establish an Illinois Labor Party. Before that Bloomington became the first test case, with Lennon leading the ticket for the "Bloomington Labor Party" for the April 1, 1919 municipal election. Bloomington was under the commissioner form of government, with each elected official operating a different city department. Lennon ran for Mayor, with four union members running for commissioner: James Nevin, Frank Morgan, Louis Salch and George Meyers. For the platform the Labor Party advocating municipal ownership of utilities, improved health and sanitation and free textbooks for school children (Labor's Choices).

The Democrats did not run a slate in 1919 but the Republicans did, attacking the union effort as socialist. In the days before the election, full-page advertisements ran in the Bloomington Pantagraph, the headline blaring "Do We Want Socialists To Govern Our City?" on March 29 and "Crush Socialism in Bloomington" on election day ("Crush Socialism," 10-11).

The opposition ads noted the Labor Party effort was not sanctioned by the AFL and attacked Lennon for running on the Socialist ticket in Denver 38 years previously. The ad said:

It's candidate for Mayor in his published remarks made in accepting his nomination, stated he was a candidate for municipal office in Denver 38 years ago upon a Socialist ticket.

Recently in a published statement, he said, They have said we are all Socialists. Well, I'm not a Socialist although I have nothing to say against Socialists.' The other four boys may be Socialists -- I don't know and I don't care -- that's their business.' ....

No matter under what party name they may be elected, if Bloomington elects a governing council dominated by Socialists and actuated by Socialistic beliefs, Bloomington will be proclaimed the world over as an American city of 30,000 people in which the Socialist predominate and are in full control of its government ("Do We Want Socialist," 11).

The Bloomington Pantagraph, normally a staunchly Republican newspaper, made no endorsement in the municipal elections, instead concentrating on referendum efforts. Commenting the day before the election, the Pantagraph noted:

Organized labor in Illinois has turned its eyes toward the Evergreen City to watch the results of the new-born Independent Labor party's first effort in politics. ....

The city election this spring is a clear-cut issue with the administration ticket led by Mayor E.E. Jones in an enforced defensive position in a non-partisan election contest. ...The contest was a clear-cut fight between the Labor ticket and the administration ticket from the primary to the wind-up tomorrow ("Results watched,"12).

The labor ticket lost by a slim 286 vote margin. Interestingly, Lennon won the male vote, incumbent mayor Edward Jones winning with female support. Votes for men and women were still counted separately in Illinois during that election. Lennon defeated Jones, 2,874 to 2,731 amongst men, but 2,309 women favored Jones, Lennon gathering 1,880 votes from women. In his election comments, Jones noted that "The spirit of patriotism has prevailed. ....I shall endeavor to serve the masses and classes alike (Pantagraph, 3)."

Lennon at least fared better than Chicago Federation of Labor leader John Fitzpatrick, who ran for Chicago mayor, only polling eight percent of the voter (Staley, 364-365).

Despite their municipal defeats, union delegates convened in Springfield on April 10 and established the Labor Party of Illinois. Defeated Bloomington commissioner candidate Louis Salch, a carpenter, served on the executive board. The group established a dues structure and adopted a platform. That November they ran candidates for the state's constitutional convention, but none were successful. The labor party convened a national meeting in Chicago in November 1919 to explore a national Labor Party, which was opposed by Gompers (Staley, 365-373).

In June 1920 the Labor Party ran statewide candidates for office, slating Illinois State Federation of Labor president John H. Walker for Governor. Lennon was slated for state treasurer. They attempted to broaden their appeal by changing the name to the Farmer-Labor Party. The party fared poorly, Walker only drawing 56,480 votes out of 2 million cast, pulling little support from Chicago. Labor withdrew its support and the party's remnants were captured by William Z. Foster and the Communists in 1923 (Staley, 373-381). John B. Lennon died on January 17, 1923 and was buried in Park Hill Cemetery, leaving his young wife and an infant son.

|