|

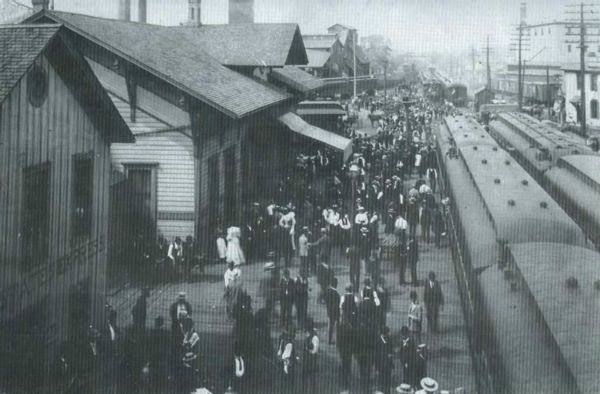

| July 4, 1894 - Trains stopped at Bloomington depot during the Pullman Boycott & strike. |

|

Although usually responding to local affairs, this newly organized federation also responded to national events, particularly if the industry involved struck close to him. On May 11, 1894 in Chicago, during a national recession, Pullman sleeping car workers struck at the company's model town south of Chicago. Pullman had cut wages during the recession but refused to lower rents in his controlled community.

The newly formed American Railway Union (ARU), led by charismatic Eugene V. Debs, former national secretary of the Locomotive Fireman, called a boycott of Pullman cars. Debs, through the ARU, was attempting to form one union for all railroad workers, rather than multiple brotherhoods. Railroad workers refused to run trains that carried Pullman cars. The railroad companies began attaching Pullman cars to mail trains, giving President Grover Cleveland a pretext to send troops into Chicago, where riots and armed clashes broke out.

Although no troops were involved, Bloomington railroad workers responded by shutting down the Chicago & Alton through Bloomington, tying up 15 passenger trains at the Bloomington depot. Local workers also used the national strike to try and win a local grievance.

On Sunday, June 26, 1894, C&A superintendent W.E. Gray had fired two brakemen and a conductor. Two days later an ARU organizer, W.C. Lynch, a former C&A brakeman, came to town and told his former fellow workers to "tie up the Chicago & Alton Railroad ("Pullman strike," 4)." The rail workers formed a new chapter of the ARU and telegraphed their national organizations about whether or not to join the strike. However, an early warning sign emerged when the Locomotive Engineers were "altogether lukewarm" about the situation.

By the time the grueling heat and humidity of the Fourth of July descended on central Illinois, 15 passenger trains were tied up at the C&A Depot, along with 1,000 stranded passengers. A trainload of refrigerated meat, losing its ice and also stuck, added to the moment's fragrance. The Trades & Labor provided transportation to the Fairgrounds and hosted the stranded travelers at the community's Fourth of July festivities. Meanwhile, railroad management ran special trains that hauled Bloomington National Guard units to protect railroad property in Joliet, Decatur and Chicago.

The Trades & Labor held a mass rally to support the Pullman strike on July 6 at Schroeder's Opera House, also asking for the removal of C&A superintendent Gray and reinstatement of the fired three workers. Despite this brave front, the Locomotive Engineers and the Fireman's lodges made their peace with Gray on July 8. The BLE had counseled its local lodges not to support the Pullman strike. These two crafts returned to work. 65 U.S. marshals were in town, accompanying each train out. Switchmen, brakemen and shop workers then scrambled to reclaim their jobs. A C&A official proclaimed, "We're going to be rigorous in taking these men back.... Those who have been the greatest agitators can hardly hope for sympathy ("Sup't Gray," 2)."

Local unions took one last shot at what they considered a betrayal by the BLE. The Trades & Labor passed a resolution, saying the BLE had "shown that lack of brotherly feeling and good judgement... We condemn the action of these brotherhoods in this struggle.... They have proven themselves treacherous to the aims of organized labor ("Trades Assembly," 4)."

If confrontations like the Pullman strike and local struggles showed organized labor's struggle against business interest, there were also more celebratory events like Labor Day.

In the late 19th and early 20th century Bloomington workers marched proudly through the city's streets. Labor Day was not only a parade, but also an opportunity for organized labor to expound its political views, as orators and speakers ended each year's parade. Besides the march, there were also concerts, dances and picnics for workers to celebrate their special holiday.

The first recorded Labor Day was the first Tuesday of September in 1882, when Peter J. McGuire of the Carpenters organized a protest in New York City against long hours and a recognition of labor's contributions. The idea proved popular, and by 1891 a number of states were officially recognizing the holiday, including Illinois. Two years later in 1894 it became a federal holiday.

The community's first celebration on September 7, 1891 was a march up Bloomington's Main Street, past the county courthouse, to Franklin Park, by about 700 workers. There prominent Democrat Adlai Stevenson I addressed the gathered throng. The next year Stevenson would campaign successfully for the vice-presidency, joining Grover Cleveland's second presidential term. Stevenson, as vice-president, presided over and signed the documents in 1894 that declared Labor Day a federal holiday.

1892 featured a grander event, setting a Labor Day pattern for the next 30 years. The day began at 9 a.m. with a courthouse band concert, followed by foot races and athletic events. At 1 p.m. the parade formed and marched for Miller Park, featuring about 1,500 participants. Union groups began the custom of wearing distinctive hats or clothing to distinguish themselves. Unorganized workers were invited to join the parade, following the main union groups, and also local businesses that the Labor Assembly allowed to participate. Once at Miller Park orations and speeches filled the afternoon, with Democrats, Republicans and Socialists each allowed a podium turn. In 1895 parade participants adopted a resolution condemning the jailing of Eugene V. Debs following the Pullman strike, and sent a resolution of sympathy to Debs. After the parade there were gymnastics, boxing and other amateur athletic performances, a balloon ascension, more music and dancing and then a fireworks display to cap the evening.

Variations on this theme followed through 1900, including a wild west show in 1898, a baseball game in 1899 and a theatrical performance in 1900.

In 1901 central Illinois unions began rotating the parade between different cities. That year over 1,000 McLean County residents rode special trains to Pontiac to march in their parade. In 1902 the parade returned to Bloomington, 1903 to Springfield, 1904 back to Bloomington, 1905 to Springfield and Peoria, 1910 to Springfield and 1914 to Peoria.

From 1907-1909 full-day celebrations were held at Hougton Lake, which included athletic events, speeches and dancing. In 1911 and 1915 the parade was held in Bloomington, and a huge crowd, 20,000 strong, marched in 1917, bolstered by unionists from Decatur and Springfield.

1918 and 1919 were the parade's last years, as all-day picnics returned from 1920-1926. A final parade was held in 1927. There was an attempt to revive the parade in 1934, canceled when a thunderstorm blew in, but the Parade did march in 1935.

Starting out with a vice-presidential candidate as the Parade's orator in 1891 set a high standard for post-parade speeches. Amongst those who followed were locally born Grand Master of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainman, P.J. Morrissey, in 1898; AFL treasurer and local labor leader John B. Lennon in 1898 and 1919; AFL secretary Frank Morrison in 1915, who spoke to 15,000 at Miller Park; Mary McDowell, Chicago's "Stockyard's Angel" in 1917, who spoke on women in the workforce; AFL organizer William Z. Foster in 1920, who later headed the U.S. Communist Party; and, Lillian Herstein, Chicago Teachers Union organizer, in 1934.

Although some speakers, like Stevenson, set a patriotic tone, the majority of speakers addressed contemporary issues. Bloomington Bulletin editor James O'Donnell, a Democrat, in 1907 condemned U.S. imperialism in the Philippines, following the Spanish American war. In 1898 Morrissey equated labor strikes to colonial Americans throwing off British rule. In 1915 Morrison noted the carnage on Europe's battlefields, comparing it to brutal health and safety conditions in American industry. Frank Gillespie, a local attorney, state senator and 1930s U.S. Congressman, spoke at the 1909, 1917, 1918, 1923 and 1934 events. In 1917 he compared labor's publicly known strikes to the "money masters' strike," which he said were secret monopoly control of markets to boost profits. (Matejka)

Even with an emerging labor movement in town, conditions for working class families could still be difficult. There was no unemployment insurance or other means of stable support during layoffs or economic downturns. Child labor was still rampant. In November 1898 Illinois factory inspector Mrs. Winnie Crissey appeared in the community and assessed the local situation:

Mrs. Crissey said last evening that she had found 200 children employed in this city between the ages of 14 and 16 years. The wages paid are very small, usually ranging from $2 to $3 a week, and in no case, so far as she has been able to find, do they exceed $3.50. As compared with other cities these wages are very low.

Mrs. Crissey found thirty violations of the law, including the eight prosecutions. She found no one who did not expressed a willingness to comply with the law. She expressed herself as very much pleased with her visit here and the courtesy with which she has been received by all. She leaves for her home in Chicago this evening ("Child Labor," 4).

Mrs. Crissey, in her prosecution of the eight cases she found, had the fine reduced to court costs, which were $4 per violation. The local state's attorney waived his fee.

|