|

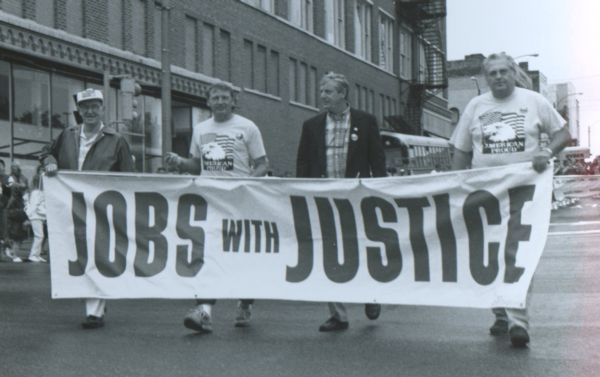

| In 1975, the Bloomington Labor Day Parade was revised. In this early 1980s photo, Nick Petri Sr. (retired railroader), John Penn, Laborers 362, Charles Stott, National AFL-CIO staff and Trades & Labor Assembly President and Laborers 362 member Ronn Morehead help lead the parade. |

|

In 1961 GE workers represented by the IUE struck, but Bloomington workers continued to work and negotiated past their contract's expiration. Lodge 1000 tried unsuccessfully to get a union shop agreement with the national firm, but did win wage increases. In October 1963 Lodge 1000 and GE negotiated a three-year pact that boosted wages two-and-one-half percent twice during the contract ("Machinists, GE," 4).

In 1966 GE workers voted by a 95 percent margin to strike the company, but a last minute settlement averted a walk-out.

1969 was the tensest labor showdown at GE; what began as a national walk-out ended in Bloomington 128 days later, the nation's last GE plant to return to work. The plant continued operation with non-union workers and management, escalating tense feelings and leading to vandalism and confrontation.

The first nationwide strike since 1946 against GE began on Oct 27, 1969, idling 147,000 workers. Bloomington's Lodge 1000 members voted 444-58 to join the national effort. A coalition of 13 unions, led by the IUE, negotiated with GE. The company claimed its "best offer" gave a 20 cent an hour increase. Bloomington, with 1,100 production and 500 office workers, had a minimum wage of $2.21 an hour, with tool and die makers at the highest scale at $4.16 an hour. The company emphasized the local plant was an "open shop." Local company spokesman Richard C. Ehrman emphasized that "People have a right to come to work as well as to picket." The company stationed a video camera to film any picket line incidents. Although extra police were present, no confrontations took place that day (Haake, A-3).

The strike drug on through the winter. Five weeks into the confrontation Bloomington Police reported nails strewn around the plant's entrance. Thanksgiving weekend saw a series of incidents. On Friday the plant was closed for eight-hours due to a power failure. Suspected was a cable thrown onto the company's power line, shorting it out. On Saturday the union's headquarters had its window shattered with a BB or pellet gun shot. That Sunday phone lines into the plant were sliced with an axe ("Phone Cables," A3).

In December workers rejected 3 percent annual raises, plus the company's earlier 20 cents per hour offer. A cost of living increase was also included. The next month, GE began offering a $1,000 reward for any information leading to a conviction about vandalism to non-union members cars or homes.

A national agreement was reached at the end of January. "I think it stinks. It's a rotten settlement and I don't think the machinists will accept it," was the reaction of Bernard Grosso, Lodge 1000's business representative. The national agreement offered a 25 percent wage increase over 40 months. Grosso predicted that Bloomington workers would reject any settlement which did not include the union shop, which the national agreement did not (Haake, A3).

In late February an agreement was reached for the local plant. It was basically similar to the national agreement and did not include a union shop.

There was never another strike at the local GE plant after the bitter 1969-70 confrontation. In 1980 the union threatened a strike over the company's use of a consultant, but that strike vote failed by seven votes. GE began reducing its Bloomington workforce in the 1980s and by the end of the decade had fewer than 400 production workers in Bloomington. The plant, with about 80 workers left, closed in 2010.

As the nation was preparing for the 1972 Presidential election and the Vietnam War dragged on, President Richard Nixon had initiated anti-inflation wage and price controls.

September 1, 1971 International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers 197 were due a 40 cent an hour increase. It was delayed because of the wage and price controls and as winter loomed, the contractors were told to by the federal Pay Board to pay it retroactively, amounting to about $300 per member for about 80 electricians.

The McLean County Electrical Contractors Association appealed the ruling; the IBEW members wanted their retroactive pay, so on January 23, 1972 they initiated a strike, led by business manager Hugh Tromp. The contractors, led by John Thoms of Gray-Trimble Electric, claimed the work done since September 1 had been done on time and material, so the extra pay was not included in their bids.

Meanwhile west coast docks were closed while Teamsters and Longshore workers battled over jurisdiction on those new container ships.

While IBEW 197 walked the picket line, freezing rain and then snow was falling.

On February 3 the strike was settled; IBEW members won their 40 cents in retroactive pay while the contractors’ appeal was pending. $4 million in construction work was idled as other trades honored the IBEW’s pickets.

In 1964 Wisconsin's Modine Corporation purchased American Furnace and Foundry in Bloomington, continuing to build the large dampers and vents that AFF traditionally made, but also adding a line of radiators for heavy equipment. Machinist Lodge 1000 representation continued with the new firm. Workers negotiated a contract with the new firm in 1968 after taking a strike vote, but did not walk off the job.

In 1974 Modine workers struck for 68-days over their contract. The walk out by 117 workers began on March 1. Average wages at the time in the plant were $3.60 an hour.

One worker, Patricia Ann Williams, was charged with attempted arson on May 3, after a fire March 21 at the loading dock of the company's East Washington Street plant. The company offered a $1,000 reward for any convictions in relations to the arson.

The dispute was settled on May 7, 1974, with workers and the company accepting a three year contract with 50 cents an hour in the first year, 27 cents in the second and 25 cents in the third. Plus an additional 39 cent adjustment was given to workers in certain job classifications. Pension benefits were expanded and a comprehensive medical plan was maintained (Haake, A3) .

When that contract expired on March 1 three years later, Modine workers again struck, this time staying out until May 23, 1977. The workers had sought a two year contract with 75 cents an hour the first year and 50 cents an hour more the second, plus a cost-of-living increase. The company offered 21 cents per hour the first year and 20 cents the second year, with a maximum ten cents annually in cost of living increases (McKinney, A3).

The union filed charges against the company in 1980, after five employees and one worker's grandchild were tested for high lead blood levels. The company agreed to a settlement that included respirators, lead monitors, daily cleaning and prohibitions on smoking and drinking in areas where lead was used. The child was exposed because of lead clinging to the affected worker's clothing.

Modine closed its Bloomington operations in 1984, moving production to non-union facilities in the southern states.

After their original job action in 1937 to gain union recognition, Eureka-Williams workers enjoyed relatively smooth labor relationships with their employer through the 1940s and 1950s. Workers did strike for 28 days in 1968, but otherwise maintained regular cost-of-living and other benefit increases from the company over the years, despite the company's sale to different employers.

Larry Yeast, business agent for Lodge 1000 during this period, reflected on a style difference between himself and his successor, Bernard Grosso, in dealing with management and bringing a company's final offer to workers:

Barney had a strike at almost every place we had -- he was pugnacious and a fighter. ...In the 37 years that I was active, I never had a strike in which I was in charge of negotiations. He told me, he says, Red, I found it that it is easier to get them out than it is to get them back in.'

I always had the policy that I wanted to know what the last offer was and what the prognosis would be if we went out on the street. How much you would have to win. At that time it was nothing to have 6-10 week strikes and if you were fighting over 2 cents, if you lose ten weeks pay, it will take an awful lot of pennies to pick that up. I was criticized for that to some extent, but I told them (the members), look, I am elected, I'm a fact-finder, ...I know things, I learn things. ...They deserve all of the advantages of what the situation is. But the people get restless too and the last contract I settled with Williams, it was almost a lost deal (1968). And I firmly believe, and I think everybody does, that they lost money at that strike (Yeast).

Yeast noted that pay increases were one thing, but also important was contract language that established grievance and arbitration systems to settle disputes in the workplace. He found out at GE in an injury case how important an arbitration system is:

We had a deal out there (at Williams), a mutual agreement, and you could almost get everything settled without a bother. You didn't have any provision that you could go to arbitration. I found ...out at GE they didn't have a provision for arbitration. There was a girl out there whose hand went into the press and lost some of her fingers and they fired her. ....So I was telling the Grand Lodge office in Chicago about it, and he says, Oh, you won't have any trouble with that, we'll arbitrate.' And I said, We don't have arbitration (Yeast).'

After Firestone Tire & Rubber opened their Normal plant in Normal, workers quickly organized United Rubber Workers (URW) Local 787 and were included in the Firestone-URW national contract. Ralph Walden, who became the local's president, remembered that plant workers overwhelming voted for union recognition and participation (Walden).

Being part of the national agreement, however, also meant they were part of national strikes. In 1967 the URW struck for 91 days and in 1976 for 129 days. Local workers were often at a disadvantage in the national negotiations. Most tire plants employed thousands of workers, while the Normal facility had 106 in 1967, 240 in 1976. Because the Normal plant made a unique product -- large, off-road tires for heavy construction and mining equipment -- their procedures and pace of work often differed from other tire plants.

On April 22, 1967 union construction workers refused to cross picket lines to continue work on an addition to the Normal plant, because of the strike. On May 31, 1967 local strikers blockaded the Normal plant during the company's lunch break after the firm announced that production personnel would make tires in the plant. Nine Normal and McLean County sheriff's police cars were at the plant that morning. At noon about 20 strikers blocked the plant's driveway until dispersed by police ("Police, Deputies," A3). Plant worker and former union officer Charles Gordon remembered the incident:

I went there one time and we held them in for about 45 minutes and it was hot. It was, it was steaming hot. They were sitting in their cars in the driveway cause we wouldn't let them out. And pretty soon I looked up over the hill and hell, there was squad cars coming from everywhere, every direction, county, city. Fellows, we're going to have break it up.' They gave us an injunction. I think we were finally limited to just five picketers. Meanwhile the companies pretty well got the judges and the court in their ballpark (Gordon).

A majority of URW members nationally ratified the 1967 pact with Firestone, but local workers voted it down, disputing the incentive rate for tire production they received locally. The 1967 contract gave Normal workers a base pay of $2.99 an hour.

Local workers also disputed the URW's 1970 agreement with Firestone, unanimously voting it down. They were over-ruled by the rest of Firestone's employees, who accepted the additional 82 cents an hour over three years.

As national negotiations were continuing in Cleveland, Local 787 members held a five day wildcat strike at the end of June, 1970. A union steward was disciplined by the company and workers walked off the job in protest (Firestone strike, A3).

Gordon and Walden both remember wildcat walk-out at the plant throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s. They said one was to force the company to install cooling fans in the plant, another over the company's displeasure with a third shift worker's long-hair. These walk-outs were not necessarily union-organized. "I think most of them (plant workers) did their own planning (of the walk-outs)," Gordon recalled. Because some of them were pretty hard to talk to. We're not going back in there, we don't care what they say.'" During another in-plant dispute a worker traveled to Decatur, picketing the large Firestone plant there, threatening to shut it down.

On April 21, 1976 the URW struck the nation's tire companies when their contracts expired. In Normal a new water pipeline was being laid from the City of Bloomington to Lake Bloomington. That morning 30-inch water pipes from the construction project blocked the company entrances. Reverend James Sims, a plant worker walking picket, said the union members had gone to breakfast and the pipes appeared. "I guess they just jumped or rolled up there. We came back from breakfast and there they were (Haake, A1)." That walk-out lasted 129 days, with local workers again opposing the contract. The national agreement allowed the Normal plant to maintain a unique definition, a "reasonable effort" clause, which affected local worker's incentive pay. The contract passed, giving workers $1.44 in increased pay over three years, plus a cost-of-living clause and improved benefits (Haake, A2).

In 1979 the URW did not strike the nation's tire makers, negotiating a contract that gave workers 72 cents an hour more over three years. 90 percent of URW Local 787 members approved the contract.

Workers continued under the national Firestone agreement until 1987, when the plant was sold to a Conyers, Georgia firm, Edwards-Warren Tire Company, which ran the plant under the America OTR label. The new company forced all workers to go through a re-hiring process, refusing to rehire some. The local union eventually won a contract in March 1988, but only after threatening a strike. The new company refused to recognize the union shop, though it did accept dues check-off and began operating 12-hour shifts. The new contract recognized seniority rights in bidding on these shifts. The workers lost two dollars an hour in pay and three dollars an hour in benefits.

In 1992 Firestone, now Japanese-owned and under the Bridgestone-Firestone label, repurchased the Normal plant. URW 787 continued negotiating for the workers but were no longer part of the national agreement.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were difficult years for industrial workers. Overseas competition and the firing by President Ronald Reagan in 1981 of the air traffic controllers put organized labor in a difficult situation.

The labor movement is the victim, manifestly, of powerful economic forces mostly beyond its capacity to control. But market competition and structural change do not automatically translate into trade union decline. ...In the view of some political economists, a new state of late capitalism has set in worldwide, displacing the regulated national economies with a global economic order characterized by capital mobility and competitive labor markets (Brody, 243-244).

Not all local workers were in a difficult situation. Construction workers, having endured a severe down-town in the early 1980s, were doing well as State Farm Insurance, Illinois State University and the new Diamond-Star Motors plant were expanding. Under the leadership of John Penn, Ronn Morehead and David Hayes of Laborers Local 362, the Trades & Labor Assembly was revived and began asserting itself in the community. Emphasizing community involvement and charitable activities, the union movement gained prominence again, especially the Labor Assembly and the Laborers local. The Labor Day Parade was revived in 1974 and the Assembly began publication of the Union News, first in 1976, which faltered, but succeeding in 1980. This was the community's first labor publication since 1956. The Economic Development Council, established in 1983, was unique in including labor as a full partner with business, education and government. Walt Petry of Plumbers and Pipefitters 99 and Penn and Morehead all served on this Council.

Labor took a more active political role during this period. In 1977 Plumbers 99 business agent Petry ran for Bloomington Mayor and Laborers Local 362 financial secretary David Penn ran for an at-large city council seat. Both were defeated. In 1979 Bloomington voted to return to the ward system and Plasterers 152 member George Kroutil and Petry won city council seats. Laborers 362 member Tom Whalen was elected to the County Board. In 1989 Petry lost his seat but Laborers Local 362 members Whalen and Michael Matejka were both successfully elected to the council from west-side wards.

|