|

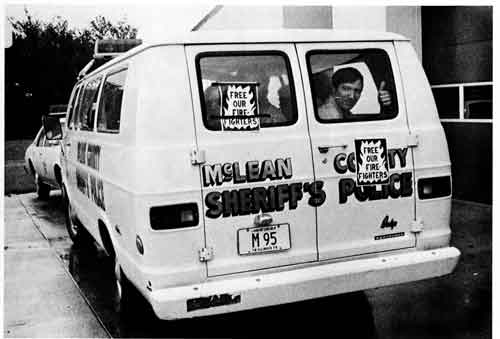

| Normal Fire Fighters being taken from the Fire Station by the county police during shift change; Fire Fighter Wayne Abbott in the van window; David Nelson photo |

|

Excerpted from "Fiery Struggle" by Michael G. Matejka, 2001, published by the Illinois Labor History Society

Introduction

"A lifetime" is how fire fighter union organizer Mike Lass described the epic 56-day struggle in Normal, Illinois.

If there was a confrontation the fire fighters were supposed to lose, a situation where the cards were in management's hands, it was Normal, Illinois. It became the longest fire fighters' strike in history and the only strike for the fire fighters, and perhaps in all of labor history, where the entire bargaining unit was jailed en masse.

Many fire fighters believed this strike was a set-up, a Seyfarth, Shaw scheme engineered to publicly defeat the union. The string of successful strikes and mounting pressure from public employees was bringing collective bargaining legislation closer at the State Capitol. Fire fighter activist felt that Normal was a planned rebuke to their emerging movement.

Fire Fighters' union attorney Dale Berry saw Normal as one place where his main legal opponent could score a victory:

We beat Seyfarth, Shaw in Danville. Then we got to Joliet and we just killed them. They were fired after that strike and so was the city manager, Lynn Neuhart, who hired them. So they were looking to regroup. And I think they picked Normal as the place that was going to be our Waterloo. Mike called me on that one, They're on strike, come on in,' so I flew down there. We were driving back to the fire station and I asked Mike, How many fire fighters?' 24.' Thinking out aloud, I said, McLean County, no other unions in the town... Boy, this is going to be a tough one.'

If Normal started out to be a rebuke, it ended up as the community where Lass' vision of a broader effort, connecting with other social movements, had its greatest flowering.

The Town of Normal was the least likely spot to find militant public employees. The white-collar community was emerging from the shadow of its twin-city neighbor, Bloomington. If Bloomington was the older community with an industrial past, definite working class neighborhoods and a small but recognizable labor movement, Normal was white, middle-class and non-union. Conservative beliefs ran deep as the dark and fertile McLean County soil in both communities. Bloomington historically had grown with the railroad and had significant industries, it had unions and a small minority population. Although Bloomington fire fighters struck in 1976, it wasn't over union recognition -- Bloomington had recognized its public employee organizations in the 1930s. Normal government proudly proclaimed its non-union status, viewing labor organizations as an anachronism of an earlier age.

In 1973 Normal's public works employees had tried to organize with AFSCME. The abortive union attempt was crushed and six workers were fired after attempting to strike.

Towering over both communities was the area's largest employer, State Farm Insurance. State Farm was also non-union, but maintained peace with its workers through a positive image and a patriarchal system that ensured employees were rewarded and secure.

Normal's immediate concern was not public workers, but the 20,000 students at Illinois State University. Normal's founder, Jesse Fell, had politically maneuvered in 1857 to bring Illinois' first public college, a "Normal" or teacher's education institution, to empty fields he owned north of Bloomington. The small campus of approximately 3,000 students was compatible with the small town until the 1960s, when the "Normal" status was dropped and the institution became a full-range university, growing quickly. Illinois State University (ISU) didn't trouble the community much with student protests, though there were a few in the antiwar heyday. Rather there was a clash between student lifestyles and small town mores, as burgeoning student apartment complexes spilled into quiet residential neighborhoods.

All this growth changed Normal. Its fire department left its volunteer past and went professional in 1969. In 1978 it had 27 members. The Town hired professional staff to run the growing community. Town council members were no longer small town neighbors, but up and coming professionals, with local government a stepping-stone in their careers.

In 1975 the fire fighters joined the IAFF, recruited by Mike Lass. The fire fighters were angry over what they perceived as broken promises from city hall. In 1977 the Town eliminated cost-of-living increases and replaced them solely with merit increases. Following the pattern of other locals around the state, Local 2442 began to push the Town for a contract and union recognition.

Local 2442's president, Ron Lawson, remembered the frustration that pushed the fire fighters to more militant action:

From 75 to 78, we were trying to get them to sit down and collectively bargain with us and get our maintenance of standards, just a written contract. That was the thrust of our strike, trying to get our first contract. It just happened we were in that process when Bloomington went on strike. It showed some people that without the protection of a labor contract they can do just about what they want to do. Our members ended up wanting to go union strictly because there were a lot of things promised to us that weren't fulfilled. They had these meet and confer' session with the city manager every year. We'd voice our displeasure, and it was never addressed. The Town eventually pushed everybody toward the union.

Throughout 1977 a seesaw pattern developed. The Town hired a law firm Seyfarth, Shaw, Fairweahter & Geraldson, which had a reputation to union partisans as a "union buster," to represent them. The fire fighters had Mike Lass and Dale Berry. The fire fighters wanted union recognition and a contract. The Town agreed to recognition -- provided they determined the bargaining unit. They wanted to exclude all officers from the union. The fire fighters, without the officers voting, voted 16-0 for the union. The fire fighters were ready to negotiate and came to the table with Captain Frank Hanover and Lieutenant Jim Watson on their team. The Town balked; they would not negotiate with the officers at the table.

Lawson recalled how critical the issue of bargaining unit composition was to a small union:

If we lost the bargaining unit issue where a 30-member department was significantly non-union, you couldn't strike, you had no leverage because they had enough people to run the department until they got new ones hired. We were either going to win or probably lose our jobs.

Who would be in the union? This issue, which had surfaced in other communities, became the critical point in Normal. The Town claimed the fire officers were management personnel; the fire fighters claimed the officers were like "working foremen," line officers who lived and worked side-by-side with fire fighters in the small department.

Questions of control were behind the bargaining unit debate. The Town claimed the fire house would be "controlled by the union" if officers were in the bargaining unit. The fire fighters knew that their union would be weak if it was limited to the fire fighters only. Exclusion would drive a wedge between the fire company's working members. Effective job actions would be difficult, as management would always have enough personnel to keep control. And in day-to-day labor-management relations, the union would be significantly weakened, because one-third of the department would be non-union.

From October 1977 through January 1978 the two sides argued about the two fire officers presence at the bargaining table. On January 26, 1978, the fire fighters voted to refuse all overtime. Frustrated, on February 17, 1978 Local 2442 took its first strike vote, 21-5, authorizing a walk out.

On February 24, Captain John McAtee was suspended and written reprimands were given to Captain Hanover, Lieutenant Watson and Lieutenant Richard Sutter for supporting the union's no overtime position by refusing to attend a staff meeting.

Three days later a one-minute negotiating session ensued. The Town staff, seeing Hanover and Watson at the table, walked out, refusing to return until the officers were off the negotiating team.

On March 2 the Bloomington & Normal Trades & Labor Assembly, the local AFL-CIO central labor council, pledged its support to the fire fighters, sending a letter to the Town, protesting its tactics. On March 7 there was a two-and-one-half hour closed door Town Council meeting, with a fire fighters' informational picket outside. On March 13, the last pre-strike bargaining session occurred, with Hanover and Watson in the room as observers. Progress was made on economic issues, but not on the bargaining unit.

On March 20 the Town Council met again, passing an ordinance forbidding the fire inspector, lieutenants, captains and chiefs from participating in union bargaining agreements. Local 2442's President, Ron Lawson, addressed the council, warning that this ordinance would precipitate a strike. Ron Ratcliffe, President of Bloomington's Local 388, also spoke, saying that Bloomington fire fighters would ignore any mutual aid calls in Normal if there was a strike. The Council passed the ordinance.

Ratcliffe's threat of no support from Bloomington was serious; there was a strong personal friendship between the Bloomington union president and Lawson. Lawson's grandfather, father and a brother were all Bloomington fire fighters, and other Normal fire fighters had family connections with trade unionists in the area.

Walk-Out

The fire fighters returned to headquarters station and wrote a letter to Mayor Richard Godfrey and City Manager David Anderson, asking the Town Council members to reconsider their position. A second strike vote was taken, resulting in a 15-8 tally, tighter than the previous 21-5 strike vote a month earlier. With no response from the Town, Local 2442 walked out at 6:30 a.m., Tuesday, March 21, 1978.

The walk out was 100 percent. Alone in the fire station was Assistant Chief Charles Smalley. Local 2442, following the example of Joliet, walked out with their turn out gear and two-way radios, promising the Chief they would respond to calls. The Assistant Chief tried to call two probationary fire fighters Jeff Feasley and Tom Elston, ordering them into the station, but there was no answer from their phones. The two were both walking the picket line.

Assistant City Manager Carl Sneed appeared and requested the fire fighters return to work, telling them their strike was illegal and they could be fired. The fire fighters refused. He ordered the two probationary fire fighters to return to work immediately. They both refused and they both were fired by Sneed on the spot.

At 8 a.m. the Town was in court. Circuit Judge William Caisley issued an "ex parte" temporary restraining order, banning the strike and naming each individual union members. The fire fighters were not notified of the hearing. Caisley set March 31 for another hearing.

On Thursday, March 23 there was a negotiating session, at the union's invitation. The two sides met for two hours but no progress was made. At 8:48 p.m. that evening the Town had its first fire call, a small electrical fire; Assistant Chief Smalley was joined by 17 strikers in suppressing the blaze. That evening the fire fighters had a long meeting, this time involving their wives and children, with very personal questions considered about mortgages, finances, support and groceries.

The next day the two sides were in court. On the strike's first day, the Town had filed a motion with Judge William Caisley for a temporary restraining order (TRO) against the strike. Unlike Judge Orenic in Joliet, Caisley granted the TRO without notice to the union or a hearing. The strike continued. Normal's counsel, Frank Miles, then filed a contempt of court petition against the fire fighters. Berry recalled:

We started out in a hole with Judge Caisley. The first time we appeared before him we were already in violation of his TRO. My approach to him was to point out that by seeking a TRO ex parte the Town had deprived him of the opportunity to hear the fire fighters' side. I tried to build him up. I cited cases to him that when a party invoked the equity jurisdiction of the court he had very broad authority to fashion an equitable remedy that was fair to both sides; he did not have to just rubber stamp the Town's request. It is a basic rule that a party that seeks equity must do equity.' Equitable relief can be denied if the party seeking it comes into court with unclean hands.' I cited cases to him where judges had conditioned an order for injunctive relief in a labor dispute on the employer's agreement to bargain in good faith. Judge Caisley was not Judge Orenic, but I think these arguments got to him. When I told him that as a judge deciding an equitable claim he was just like a King's Equity Chancellor, he sat up a little straighter.

Judge Caisley postponed a decision on the Town's motion and ordered the two sides to bargain. He told the Town to rehire probationary fire fighters Elston and Feasley.

On Saturday, March 26, the fire fighters responded to three different calls. Two were within five minutes of each other, so striking fire fighters entered Station 2 and started the trucks, responding to the alarms. The small fire department actually had more fire fighters responding to calls during the strike then they did during regular operations. Fire Chief George Cermak told the Pantagraph, "We do have a pretty good level of coverage now."

At 8 p.m. on Easter Sunday, March 27, both sides again appeared before Caisley. They reported progress on 19 items in negotiations, but no movement on officers. The union agreed to exclude the Assistant Chief from the unit. Caisley ordered further negotiations.

On Monday morning, March 27, both sides were in court again. Caisley took testimony from the Fire Chief, City Manager, Assistant City Manager and all the fire fighters, who testified they were willing to fight fires, even while on strike. Two fire fighters testified that Assistant City Manager Sneed had told them the Town was willing to "let buildings burn" before it would include officers in the bargaining unit. Caisley deferred action, ordered further negotiations and asked both sides to return the next day. The next day the fire fighters returned, still with no progress. But that day's hearing was interrupted by a fire call, and the strikers ran from the courtroom, responding to a false alarm at a nursing home. 20 minutes later they returned. At that point Caisley found the striking fire fighters in contempt of court, ordering them to return to work by noon. He ordered the local union to pay $1,820 in probation costs, the Town $2,600. The fire fighters adjourned to a room and discussed their options.

Berry recalled:

At that point it seemed to me that Judge Caisley was trying to be more evenhanded, so I told them men I did not think it would be a good move to flatly deny Judge Caisley. So I recommended they consider a return to work.

Ron Lawson returned from the huddle and told Judge Caisley the fire fighters would return to work until 8 a.m. the next morning. If there was no contract, the strike would resume.

The union negotiating team returned to work at Station 2, across the street from the Town Hall. 150 pickets, including fire fighters and their families, other union members and ISU students, surrounded the station, holding a candle light vigil. A state mediator, Ed Schultz, arrived, shuttled between the two sides, each ensconced within their own building. Negotiations ended at 3:30 a.m., with no settlement. At 8 a.m. the strike resumed. Berry said he did not expect substantial progress at the session:

The return to work was a concession to Judge Caisley. The union did not have any illusions that it would have much effect on the Town. The Town basically stonewalled. They figured time was on their side and if they held fast, Judge Caisley would have no alternative but to hold the men in contempt.

That afternoon further legal hearings resumed and Judge Caisley ordered the county's probation officer to revoke the probation of those strikers who failed to appear to work that morning. Again the court action was interrupted by a fire call, with the strikers responding.

On Thursday, March 30, over half of Normal's Public Works Department called in sick, an obvious sympathy strike. Bloomington's public workers refused to cross fire fighter picket lines at the landfill. And five Bloomington fire fighters were given one-day suspensions, for refusing to answer a mutual aid call from Normal.

With all fire fighters having broken probation, Caisley called a hearing for 1 p.m., March 31. Each fire fighter was called before the bench and was asked whether or not he was aware that he was in contempt. All stood and admitted their guilt. Lawson said, "the Town is holding this court proceeding over our heads. Even if we're put in jail, we won't go back to work without a contract."

Caisley turned to Berry, asking for his position. Berry argued that the fire fighter strike was an act of civil disobedience in support of a fair contract. If the court felt it necessary to apply a sanction, then it should sentence the bargaining team to jail and order the Town to continue negotiations.

Before the sentencing began one fire fighter, Richard Sylvester, who had medical problems, purged himself of contempt, saying he would take sick leave for the strike's duration. Captain John McAtee, who was on vacation when the contempt citation was issued, asked to be added to it, since he had joined the strike upon his return. Caisley refused. Wayne Abbott, a fire fighter who had gotten sick his first day on the picket line, rose and addressed the court, saying, "I never understood what black people went through in this country. Now I know."

Caisley then announced his ruling. He shocked everyone speechless with his sentence for the bargaining team, 42 days in jail. But he did not stop with the bargaining team. He then took matters a step further than any judge had ever done before. He sentenced all the remaining fire fighters to 42 days in jail for contempt of court. He declared the Town's station a "work release center" and split the fire fighters into two shifts, each sentenced to 21 days of "work release" and 21 days in jail. The Town was charged with all costs, including the regular wages for the strikers plus overtime and also extra costs of incarceration and extra deputies.

Local 2442; 24 fire fighters -- 42 days in jail. Perhaps Judge Caisley thought his unique sentence would force both sides to the table; few believed the fire fighters would serve the full 42 days. There was no time for wonder though, as County Sheriff John King and his deputies immediately swung into action. He pushed the fire fighters back into the holding areas, not even giving them time to speak to their families or hand over car keys. Stunned family members and supporters stared in wonder as Normal's Fire Department was herded to jail and handed their prison jumpsuits. It was the beginning of a totally new experience for law-abiding fire fighters.

Berry recalled that the Judge's action was totally unexpected, a new twist that the fire fighters were not prepared for:

We expected just to be held in contempt and the (negotiating team) put in jail. When we came back in and he said, You get 42 days,' that shocked everybody. Nobody thought of 42 days. The whole experience had been a week. It would be over in a week. They took them all away. It was a pretty devastating experience. They just took them away.

What we really had was an 84-hour work week, 24 on and 24 off. And the positive part of that was it was a form of a Silver Spanner strike. We didn't have any direct control but we were still doing the work. One of the costs for the Town, which was part of Caisley's order that we really liked, was the Town had to pay 28 hours of overtime every week for each man.

The Town of Normal had gained a valuable weapon -- time. Six weeks in jail; six weeks to wear the fire fighters down; six weeks away from friends and family and familiar routine to break the fire fighters' spirit.

Lawson remembered expecting to go to jail as the union president, but not to have his whole union behind bars:

When they sentenced the whole fire department to jail, now you got guys in shock. They completely isolated the negotiating team. The negotiating team was jailed 42 consecutive days and the rest of the members were divided into equal numbers and were jailed for 24 hours and in the station for 24 hours. It threw a monkey wrench in it when he sentenced everybody, now we had nobody to walk pickets, we weren't prepared at the that time for our whole union to be put in jail.

That afternoon half the fire fighters were transported in a jail van, under guard, to the familiar environment of Station 1 -- now a "work release center." That evening the Town came back for its court-ordered negotiations. Expecting repentant fire fighters, the Town returned to its original bargaining position, withdrawing its offer of lieutenants in the bargaining unit. The Town would not offer amnesty; it promised no firings but would not promise there would be no other disciplinary actions. And finally, it offered the fire officers, if they were truly serious about being in a union, the opportunity to take demotions to fire fighter rank, and leave other, non-union individuals to fill the officers' position.

If the Town of Normal expected submission, its latest offer only brought increased anger. The fire fighters were now convinced this was no longer a negotiating process, but an outright attempt to break their union. Lawson felt the Town was ignoring the Judge's admonition to them to negotiate, bent instead on breaking the union:

I talked to Caisley, he had no idea that sentence would be completely carried out. He thought he ordered the Town to come in and negotiate with us at jail, his way of saying (to them), You're not out of the woods, you're not solely the good guys in this, I'm going to order you to come to jail and get this thing settled.' He sentenced us to jail because we were in contempt of court. He had no idea we were going to serve that whole sentence out. And we didn't either. That's how Seyfarth, Shaw and the Town were on an all out union bust. They wanted to control this fire department and they did not want unions in this town. And boom, they were not going to have it. They were entrenched now and it's a war, we know now, we went on strike, we're not going to have a job unless we get this thing settled. Caisley, I felt sorry for him, because he had no idea.

I believe after the initial shock it strengthened the guys. The Town is your biggest ally, because they'll always do something to turn the men, the fence walkers, the non-militants, they always do something to push them over to your side and that really did. We had guys like Wayne Abbott, one of the mildest mannered guys you'd ever want to see. His heart was fire department. He really questioned us, when we went out, about how we were going to provide adequate fire protection. He was one of the guys that really had a hard time walking out the door, for legitimate reasons. When this happened, Wayne ended up being one of our strongest. They polarized it and he ended up being one of our strongest men.

Student supporters

A unique hallmark of the strike entered that evening. About 30 Illinois State University students held a candlelight vigil outside the university's administration building, talking of a "sleep-in" to draw attention to inadequate fire protection. They debated their next move, perhaps marching on the University's President's house, doing something to help pressure Normal's largest institution and employer. They finally resolved to march on the fire station where the jailed fire fighters were and show support.

The students were primarily female, mostly but not exclusively from the university's Catholic "Newman Center." Fr. Joseph J. Kelly and Sr. Marilyn Ring taught them Catholic social justice beliefs -- support for farm workers, nuclear disarmament and solidarity with embattled Third World peoples. For the last week they had met with both Town staff and the fire fighters, trying to understand the issue, and had also attended the court hearings. It was an easy leap to transfer their ideals to the jailed fire fighters, seen as victims of municipal, not corporate power. Another support contingent came from the community's 60s leftists, who also became visible strike supporters. Fire fighters expected their families and other unions to support them, but here was a new, and very vocal group, joining their cause.

At 11 p.m. that evening the students marched from the University's quad to station number 1, where one-half of the now jailed fire fighters were serving their "work release." One lone fighter, standing by the equipment door, spotted them and soon a rebel yell echoed within the fire station, as fire fighters gathered by the equipment door to welcome their new found support. Rewriting a Barbra Streisand hit, "Make Your Own Kind of Music," the students sang:

Make your own kind of contract,

Sing your own special song,

Make your own kind of contract,

even if Town Council won't sing along.

After exhausting their repertoire of rewritten songs, the new found supporters debated their next move. Should they hold another vigil like this? They decided to do so, but not at night. Rather, they would regroup at 8 a.m., when the second group of fire fighters would be brought into the station.

So at 8 a.m. the next morning, a small group of students with their guitars, singing their songs again, were joined by fire fighters wives, cheering support to the fire fighters, who gathered a few quick words or hugs with their children and wives at the station's back door. A daily tradition was born that would last throughout the strike.

That morning the Town Council was holding a work session; a few wives kept vigil at city hall and confronted Council members and staff. Each action of this type emboldened these women, who soon became the strike's visible and most public force while their striking husbands were locked up.

Trying to move things forward, local union leaders met that morning with State Representative Gerald Bradley, the area's only elected Democrat, to try and use his influence to push negotiations. Bradley agreed to meet with Normal's Mayor Godfrey and encourage his direct involvement in negotiations, rather than simply the Town's staff. Another negotiating session with Town staff occurred in the jail that afternoon, the Town held to its no officers in the bargaining unit line and demanded reduced wages and benefits in exchange for a contract.

Berry saw Seyfarth, Shaw's manipulation in the Town's regressive stance, cutting back already negotiated items at each meeting:

This was a very definite effort at defeat, to crush our movement. They didn't want to bend. I'm sure Seyfarth, Shaw was part of that. They saw what we were doing and they wanted to beat us, mainly to discredit Mike and me. They pulled out all of the stops, they weren't going to settle for anything.

The Town staff was united, there seemed to be no weak link. Without an elected official in the room, political pressure would be hard to apply. If the Town only outlasted the fire fighters and jail wore down the fire fighters, perhaps the strike could be broken.

Mike Lass decided to pierce that armor, find the weak link. He began a battle of wits and nerve with the Town's attorney Frank Miles, a calm, quiet lawyer, who affected a very professional demeanor. Lass began to question Miles' sexuality, reminding him that masturbation caused hearing loss and brain damage. At opportune moments when the Town was pushing a new demand, Lass would simply frown at Miles, shake his head and move his hand in an up and down motion. Miles was infuriated, but couldn't "sink to this level." Mike Lass was looking for a way to psychologically crack the armor and move the negotiations forward.

Gerald Bradley emerged later that day, announcing that Mayor Godfrey would meet with the fire fighters -- but without Lass or Berry or their own negotiating team. Lass was infuriated, lashing out at a divide-and-conquer tactic and accusing Bradley and the local union officials who had called Bradley of a set-up. Nevertheless, the union accepted the offer. The union's leadership was confident the rank and file could stand up to the Town. If they did successfully, it would demonstrate the unit's cohesion. The rank and file fire fighters met with the Mayor, City Manager Anderson and Council member Paul Mattingly. The fire fighters held fast to their demands and no movement came -- but the Town had pumped their hopes up by agreeing to a meeting and had let them down again.

That night over dinner Lass sketching on a napkin came up with a logo for the strike. Jailed fire fighter Craig Wall, an artist, transformed it into an image, a circle with Local 2442 on it, the number split down the middle with "24 men" on a red field on one side and "42 days in jail" on a blue field with bars behind it on the circle's other half. Printed in white around the logo's circumference was the slogan: "A fair contract key to fire fighters' freedom." This logo would soon appear on buttons, bumper stickers and posters throughout the Town.

Sunday Normal's non-union public works employees held a food drive and gathered 50 bags of groceries for the fire fighters. On Monday the City Council was scheduled to meet. That morning the fire fighters attracted their first national attention, as ABC News filmed their early morning demonstration at the fire station. That afternoon the strike suffered a casualty, as fire fighter Vance Emmert signed an affidavit, saying he would return to work. He was purged of contempt and released from jail.

Taking over City Hall

Despite that defection, Normal's Town Hall was crowded that night, as fire fighters from throughout Illinois, local unionists, students and family members gathered outside the chambers for a rally. Over 200 packed the tiny chamber and loudly chanted "Free Our Fire Fighters" when the council entered. They quieted for the pledge of allegiance. Godfrey said no one would be allowed to speak but that city council members would be allowed to comment on the strike. Council members Jocelyn Bell and Paul Harmon attacked Lass and Berry as "outside agitators." This drove the crowd to a chanting, screaming frenzy and the Council retreated from the chambers.

Captain John McAtee followed them and asked if he could reply. He stirred the crowd anew with his speech and accused the Council of misusing its powers. He appealed to the Council to allow room for movement: "You've got these men against the wall; all they can do is give in and crawl back to their jobs."

Godfrey's reply was drowned out; the Council recessed for 15 minutes again and then attempted to resume business before being drowned out. They finally adjourned to an executive session, leaving their chambers to newly energized supporters, who took the Council members' chairs and sentenced the Town Council to "42 days in jail." Eventually Normal's police cleared the chambers, but the fire fighters' struggle took on new and deeper meaning to a larger crowd that night, a mixed group of trade unionists, student activists and fire fighters' family that would coalesce into an active, supportive coalition. Most Normal Town Council meetings were sleepy affairs; no one had ever packed the chambers before and prevented a meeting. These were premonitions that the fire fighters' effort would not be quietly broken.

The next day another two-and-one-half-hour negotiating session took place, but no more movement was reported. The fire fighters were getting no "special treatment" from Sheriff King. The regular prison regimen included limited visiting and being doused for lice. Jail visits were limited to five one-half hour meetings weekly. This was most hard on the negotiating team members, who were not released to the fire station every other day. They could not use the fire station phone to call their family or chat at the door; they did not see the cheering crowds. Their only respite was the family visits, reports from other fire fighters, daily meetings with their attorney Berry and the increasingly infrequent negotiation, which ended on April 6. The war of attrition and nerves, now increasingly fought in the public arena but also in each fire fighter's heart every time the jail cell door clanged shut, intensified.

Lawson remembered the isolation of jail and its effects:

It affected a lot of people differently. It didn't bother me, other than being away from my family and friends. I got letters from Ronnie (Ratcliffe), you can't believe what a letter would do for you. I don't know how many letters he wrote me and all he would do is tell me what's going on. You tell your membership, Stay together, stay strong,' and he was telling me, Just hang in there, everything is going to be all right and we'll take care of things out here.' We had to rely on Mike and Dale to tell us and they kept us appraised pretty well of what was going on.

On a blustery Saturday morning, April 8, over 200 supporters gathered at 7:30 a.m. to greet the fire fighters. Harl Ray, Illinois AFL-CIO lobbyist, spoke to the crowd, along with McAtee. A delegation of a fire fighter's wives, a student and a union member called on each of Normal's businesses that afternoon, asking them to sign a petition supporting the fire fighters and to put a sign in their window. About 70 signed the petition, but few took the signs. The community's newspaper, the Bloomington Pantagraph, editorially chastised this effort in "No Children's Crusade."

Certainly, the striking firemen...seek sympathy and public support for their cause, even if the cause is vague and confused. No doubt children of firemen who are spending time in jail are unhappy. ...But firemen have chosen this role for themselves and for their families. They cannot in good conscience use children to convince Normal residents that villainy of others produced their trouble. ...We urge the firemen to end the strike. Neither the government nor the citizenry of Normal seek serfdom for them or denial of organizational rights. It is just that employees must not dictate terms of employment to the public employer.

The newspaper followed with another editorial a few days later, when Lass and Berry, accompanied by the AFL-CIO's Harl Ray, met with legislators to cut ISU's funding unless the strike was settled:

And what do their labors in behalf of Normal firemen make Normal firemen? Dupes, that's what. These two and others in the labor organizations of the state are doing their damndest to turn a group of decent ordinary Normal firemen into a cause celebre. The next phrase we may hear from the Fire Fighters organizer, or the labor attorney, could well be Save the Normal 24' or whatever.

Can Kunstler be far behind?

The only comforting fact is that their efforts will fail. The tragedy is that Normal firemen are paying most of the costs.

The Town tried to divide the fire fighters on Friday, April 14, when they resumed negotiations. The Town publicly announced that morning that their "final offer" was being presented to the fire fighters. Lieutenants were allowed in the bargaining unit, but fire captains were out, allowed to take a pay cut and start again as fire fighters. There was an amnesty provision but also a reduced fringe benefit package which the fire fighters had previously rejected. What infuriated the fire fighters and steeled their resolve was that the Town had given the jailed fire fighters, but not their negotiating team, a copy of the proposal first, and then also sent a letter to the fire fighters' wives, outlining a completely different proposal.

The next morning the fire fighters met together at Station 1, after the shift change, and debated the Town's proposal. The union invited Judge Caisley to conduct a secret ballot vote. Each member cast his ballot. Judge Caisley retired to count the ballots and appeared to announce the result to the expectant assemblage. With a slight smile on his lips he solemnly intoned: Yes - 0, No-23. After two weeks in jail the union had unanimously rejected, the Town's final offer. The fire fighters stayed together for four more hours and drafted a counterproposal to the Town.

Monday, April 17 was another Town Council meeting. In downtown Chicago that morning, members of Chicago Local 2 and Aurora Local 99 picketed the law offices of Seyfarth, Shaw, Fairweather and Geraldson in support of the jailed strikers. The Town got more negative publicity that morning when Republican Governor James Thompson, who was forging ties with organized labor, announced at a Peoria press conference that he was turning down Mayor Godfrey's request to send the National Guard into Normal and that he would never send the National Guard in during a strike.

This infuriated Normal's mayor, who claimed he had called the Governor's office only asking what the procedure was for calling out the Guard, not for it dispatch. At that night's Council meeting a large crowd gathered outside the door but no disruption of the meeting was allowed as 70 state troopers, all the Town's officers and ISU's police force stood guard. The massive display of force was made to look ridiculous when the student supporters staged a guerrilla theater in the middle of the street for the crowd of over 400. Only 81 attendees were allowed in the meeting, the Town citing its fire code capacity for the room. Captain McAtee had asked for permission to address the Council and did, presenting 2,500 signatures supporting the fire fighters -- more Normal residents than had voted in the last municipal election. McAtee was followed by Local 2442's President's wife, Pam Lawson, who attacked the Council for sending their misleading "final offer" letter to the spouses, calling the Town's action "degrading to our character and phony as a three dollar bill."

On April 19 the Town released a "report" on the strike, reiterating their positions and noting that: "The Council examined, in detail, the possibility that the parties may not reach an agreement and, consequently, the fire fighters may not return to work." The next day various fire fighter locals from around the state took turns picketing Normal's Town Hall.

Building Union Spirit

With no negotiations, Lass immersed the fire fighters in labor history. Those in the fire station watched the documentary film on Kentucky coal miners, "Harlan County, USA," showing on cable TV. The Amalgamated Clothing Workers 1963 labor documentary film, "The Inheritance," was shown to both shifts and wives. The local underground newspaper, the Post- Amerikan, came out with a special edition, which the fire fighters paid to reprint in the thousands, including strike stories and a strike chronology, but also labor history of long-forgotten local battles. Inside the county jail Ron Lawson was reading about Eugene Debs. Fire fighter Rick Horath, who frequently posted encouraging signs on the station wall, produced another: "This is nothing compared to those who lost their lives in the labor struggles of the 1930s. Which side are you on?" Horath also coined a new slogan that captured the strikers' growing determination. Councilwoman Jocelyn Bell had been quoted that she could see "a light at the end of the tunnel." Horath defiantly extended the metaphor, "Yea -- the lights of an oncoming train -- engine 2442!"

Rather than negotiations, on April 25 the Town filed a lawsuit against the IAFF, asking for $276,000 in damages from the International Union, Local 2442 and Mike Lass. "This suit is being filed not out of any vindictiveness to the striking fire fighters or their families, but because it is the Town's belief that those who cause and continue an unlawful strike should be the ones who pay the extraordinary expenses it generates. That burden should not fall on the general taxpaying public of this community." The case never actually came to a courtroom hearing. Berry and Lass called a press conference, deriding the suit as a feeble attempt to intimidate the strikers.

Attempting to move negotiations, Judge Caisley suggested mediation. This too stalemated as the fire fighters wanted binding arbitration, the Town only advisory. John Penn of the Laborers local approached Lass with the idea of a "citizen's review board" made up of prominently local citizens, allowing the fire fighters to return to work under their old conditions. When the Pantagraph editorially announced and endorsed the idea the next day, Lass again charged the local unionists of "backdooring" him. The various proposals caused some dissension in fire fighter ranks, as many members were anxious and ready to end their jail sentence. Penn continued to meet privately with Caisley and Mayor Godfrey, trying to formulate a compromise. If Penn had a difficult task selling Lass on an alternative, Godfrey was in a similar position with his own entrenched staff and Council.

Throughout the interminable process, the Town kept a plan to fire and replace the fire fighters as an active option. This took on added meaning when the Town began advertising for fire department applicants. The union responded, not with fear, but again by frustrating the Town's plans. Since it cost the Town about $30 to process an application, numerous union members, fire fighter supporters and even Lass and Berry signed up for the test. Ron Ratcliffe, President of Bloomington Fire Fighters Local 388 and a close personal friend of Ron Lawson's, also signed up. He listed his three references as Lawson, Berry and Lass.

Will Bloomington strike?

Ratcliffe had other things on his mind, though, besides supporting his friends in Normal. Bloomington's contract was up on May 1, 1978. Two years previous, with Lass in town and with Normal's City Manager, Dave Anderson, acting as "metro-manager" for both Bloomington and Normal, Bloomington's fire fighters had struck for one day. This time the fire fighters united with Bloomington's water works and public service employees in contract negotiations. Lass got the three unions to form a coalition and coined an anagram for the new grouping -- City Unions for Bloomington Employees (CUBE). Rumors abounded about deadlocked negotiations and the public employee strike spreading to Bloomington. Perhaps another strike would force a resolution to Normal's problems.

Wednesday, April 26 saw another mass rally outside the fire station. The state convention of the AFFI adjourned from Decatur and rode buses to Normal to show their support to the imprisoned strikers. The student supporters sang songs for the conventioneers and re-enacted their guerrilla theater from the previous Town Council meeting. IAFF President William "Howie" McClennan flew into Bloomington to address the crowd. Striker Ken Kerfoot's wife Donna, speaking for the families, addressed the audience, particularly touching on the Town's letter to the families. "The Town thought they were dealing with weak and stupid women. Wrong! We wives are just as determined, intelligent and just as tough as our tough husbands."

Before returning to Decatur, the conventioneers gathered en masse outside the county jail, where whoops greeted them from inside. McClennan met with the strikers inside and wept as he heard their stories.

Two days later another striker, inspector Garry Broughton, signed an affidavit and was released from jail. The fire inspector's position was now out of the bargaining unit and it became a management position. The jail term was coming to an end, but many fire fighters began to wonder. If a few more cracked, particularly officers, could the Town run the department without them?

On April 29, Bloomington's public employee unions, united in CUBE, took a strike vote and authorized a walk out if their contract wasn't resolved. The three unions agreed none would settle until all three reached an agreement. Working without a contract but with continued negotiations, Bloomington's three public employee unions won an exceptionally generous contract by May 5. After an all-night negotiation, the union bargainers went out for breakfast, congratulating each other heartedly. Ron Ratcliffe sat silently and eventually walked out on the group. He knew Normal's strongest potential weapon -- a general public employee shut down between the two cities -- was now gone. His friends were isolated. Ratcliffe remembered:

We got a really good contract that year, probably one of the best we've ever done. Of course, inflation then was 10-12 percent. Bloomington just didn't want to take the chance, they were going to give us a fair contract and they did. I remember being personally disappointed that we got such a good offer, because down inside there was a part of me that wanted to go out on strike. I know I'm weird, but I got a real adrenaline rush, there was part of me, I hope we don't settle.' But we did. I'm not stupid to go back and say, Look, we're going to take a strike vote.' They're not going to listen to me anyway.

As an International union representative, Mike Lass was duty bound to negotiate and consummate a good contract with Bloomington, which he had done. Later that morning he drove aimlessly around the city, having helped Bloomington successfully negotiate their contract. He quietly admitted things didn't look good. Local 2442's chances were 50/50 now, he felt, and he expected the Town to import strikebreakers soon. Rumors were flying to that effect. Finally, Lass having talked through all the possible options, had only one: continue the course. "It's too late to go back now," he shrugged.

The Back Door

Sunday, May 7, was a wet, driving cold morning. Only a faithful remnant of about 12 greeted the fire fighters at their shift change. Mike Lass was nowhere in sight and two strange men in suits were in the station with Judge Caisley. The alternate shift did not return to the jail. Someone ran to strike headquarters at the Falcon Motel and hustled Lass out of bed.

One of the two men in the station was Lass' boss, Anthony Delgado, IAFF Director of Organizing. The fire fighters inside were tense, haggard, frustrated with no negotiations. For 48 days they had been on strike, jailed, and seen no movement in negotiations. The suffering and embarrassment of jail wore them down, while rumors of firing and replacement ate at their spirit. Caisley wanted a proposal to carry to the Town. Despite a long, often angry session, the fire fighters stuck together. They still wanted the captains in the bargaining unit. They did agree to a future no-strike clause for captains, backed up by a bond and a heavy financial penalty to the union if they did. Caisley, a generally good-natured individual and not hostile to the fire fighters, carried their proposal back to the Town Hall.

Berry said that he and Lass had primed the fire fighters to be cautious toward the International union's involvement, fearing a recurrence of the "back door" they claimed ambushed them in Springfield:

Gannon was there. Because of the publicity, the International was there. Gannon came into town, pretty early in negotiations and I remember we were at strike headquarters, the Falcon Motel. The local was already primed and understood the issues. He was there for a few days and we said, Got to have a meeting.' So we invited him into the back room at the Falcon, all the executive board was there. Ron (Lawson) laid it out: We're happy you're here and appreciate your help but you got to understand there are certain ground rules. The local will determine the issues and no contacts are to be made with the Town unless the executive board specifically approves it.' The next day he was gone. It would have been good to have the Eighth District vice-president helping you, but it was one less thing to worry about.

That afternoon the Town did its physical agility tests for its new applicants. About 20 strike supporters were among the 40 trying out for the department. Only a few of the supporters completed the entire testing process. Amazingly, one of them ended up number one on the department's eligibility list. At 5 feet, three inches tall and weighing in at 112 pounds, most fire fighters and their families were used to seeing ISU student Lucia Dryanksi outside the station with her guitar, singing union songs. Would this strike bring another change to Normal's department, its first woman? Dryanski never did join the department, but the speculation gave the fire fighters and their families another new reality to consider.

That night Donna Kerfoot repeated her speech from the convention rally in Chicago, at the annual Democratic Socialist "Debs-Thomas Dinner," a mainstay event of the Chicago left. Her fiery words and strong statement, at the same time Illinois was wrestling with the Equal Rights Amendment, brought down the house. The five women who traveled to Chicago came home with $300 more to bolster the strike fund.

The next morning, Monday, May 8, the Town Council was expected to respond to the fire fighters' offer that Caisley had transmitted the previous morning. At 9 a.m. the fire fighters' wives and supporters gathered, the whole Town Council and staff present.

The Eagles have landed

Mayor Godfrey, reading from a prepared statement, didn't respond to the offer -- he dropped a bomb that threatened the whole strike. He first refused any new negotiations, saying the town's "final offer" from April 14 still stood. If 11 fire fighters would accept it, the Town would too and view it as a legitimate contract. On Thursday the fire fighters jail sentence ended. If they did not return to work by 8:30 a.m. the following Monday, "their cases will be referred to the Police and Fire Commission....for action deemed appropriate for that body."

And then, to further heighten the situation, Godfrey announced:

The Town has today authorized execution of a six month, renewable contract for fire suppression services with a private corporation comprised of professional fire fighters, that firm being Eagle 9-11, Incorporated. There are presently members of that fire service on duty in Normal.

The room exploded. Wives ran screaming at the council members, repeating their promises that their fire fighter husbands would never be fired. Lass chased the Town's attorney, Frank Miles, into the restroom, shouting at him the whole way until someone physically restrained him. The Fire Chief, George Cermak, who had promised the families outsiders would never come in, was also confronted and quickly exited, spending the rest of the day incommunicado in his home. The three local Laborers leaders present, Penn, Ron Morehead and David Hayes, president of the central labor council, sat silently, shaking their heads. A line in the sand had been crossed, strike breakers were in town. A reaction was imminent. The women poured out of the station, screaming and pounding on Normal Number 2 station, a small corrugated building beside the town hall. This is where Eagle 9-11's employees were at. Police restrained and blocked them.

A furious Mike Lass returned to the Falcon Motel, ripping the "No Violence" sign from the wall. Normal police cars were everywhere that afternoon, outside the fire stations, the fire chief's home, cruising the Falcon's parking lot. Police lieutenant Denny Kamp stopped at the Falcon and pleaded with the fire fighters' families for no violence, saying neither he nor his fellow officers wanted to be in the middle.

The women and one male supporter (your author) returned to station two, pounding on the walls, screaming "Scab!" and challenging the "eagles" to come out and "fight like a man." Within ten minutes four squad cars pulled up and Normal Police chief, Richard McGuire, emerged seething from his car, telling the women "picketing was illegal on public property." The male supporter reminded the chief that "picketing was legal, as long as no one's entrance or exit was blocked." The chief exploded in a tirade about brick-throwing campus troublemakers, threatening punishment. He repeated his warning to the wives, allowing picketing, but threatening to arrest the first one who touched the building for disturbing the peace. Turning his back on the now quiet group, McGuire walked toward his car. At that moment Pam Lawson screamed "SSSSCCCCAAABBB!" at the top of her lungs. The police chief turned, glared, his muscles tense, sputtered to speak and then returned to his car. That was the last time demonstrators outside station two were confronted by police in what turned into a very long and busy night.

Meanwhile Lass was further confused and angered when he heard Miles was on his way to Caisley's court, asking for an early release of the strikers. In the courtroom an odd spectacle played out as the Town asked to release the jailed fire fighters, while the fire fighters' attorney, Berry, argued that they stay in jail. Lass and Berry feared that early release would find the strikers converging on the strikebreakers, giving the Town an excuse to arrest them for disorderly conduct or assault and then fire them. Caisley reiterated his original sentence: release after 42 days, a signed contract, or individual affidavits. The strikers stayed in jail.

A crowd of unionists, students and fire fighter families gathered outside station two that afternoon. When city manager Anderson visited the strikebreakers, Lass tried to provoke a fight with him, butting him in the stomach and shouting, "Come on! You want violence! I'll fight you here and now!" Anderson ignored him and Lass finally realized that violence is what the Town wanted. The media was allowed to interview the "eagles" that afternoon and John Penn of the Laborers, using a Labor Press card, joined the group. In dialoguing with the "eagles" Penn ascertained that they were recent fire school graduates, some from Colorado. They didn't know about the jailing and fire fighters still on duty. They were told Normal was recovering from a disastrous strike where fire protection was refused and the strikers refused to return to work. Eagle 9-11 was not incorporated in Illinois, but traced to Laurel, Maryland, headed by the former DeKalb, Illinois fire chief.

All night long rocks and pebbles bounced off the walls and roofs of station two, along with shouted chants and threats. Supper was hard to cook, as the gas was turned off, soon followed by a cut cable TV line. Bloomington fire fighters used their mutual aid agreement radio to talk with the "eagles." "Are you guys from Colorado?" "Yes," would come the reply. "You know, they used to hang scabs in Colorado." Ron Ratcliffe, on duty that night, called hourly, reminding the strikebreakers how many hours until he was off duty and would "pay them a visit." Squad cars zoomed by all night but none stopped.

Ratcliffe and Lawson remembered that evening as a turning point, mobilizing union support to a stronger level. Ratcliffe said:

It wasn't just Bloomington fire fighters. We had Machinists 1000, AFSCME 699, Laborers 362. There were bartenders, painters, Rubber Workers, there were people from every union in town. When they brought in Eagle 911, that was probably the biggest mistake the Town of Normal ever made because that just polarized. It had to be intimidating for those people inside there, saying, What the hell are we getting into?' We were beating on the sides of the building. One guy went around and disconnected their phone and their cable, shut off their utilities. It was something.

Lawson added:

It polarized but it also united the labor people, and frankly, just pissed everybody off. Those people, they left town, just scared to death. All labor realized they were trying to replace the fire fighters in Normal with scabs. Now all of labor, a lot of people didn't know what the issue was, didn't really care, but when they bring in outside people to take our jobs, other unions realize this is a union-breaking issue. They could identify with scabs coming in to take your jobs. That really unified the unions in town when they brought in the outsiders.

The next morning the three "eagles" wanted out. A covered truck backed into the station and took them to the airport. Normal refused to admit their flight and an even larger crowd gathered that night. Finally, after two hours of wall pounding and threats, an off-duty Bloomington fire fighter was allowed to inspect the building. "All clear." The crowd dispersed. Normal had played its biggest cards -- replacement -- and it failed. It was a calculated, powerful move, but made too soon. With the strikers still in jail and performing mandatory fire service, importing strikebreakers convinced many that Normal's true agenda was union busting.

Berry felt that Normal exposed its true intentions by bringing in strikebreakers:

That was an irresponsible act. It was done as a strike tactic. They would take control for the sole and overriding purpose of breaking the union. What would get lost in that process was the work. Why do you have a fire department? To put out fires. And who do you have to do it? You have capable people. What Normal did was force their strategy to an extreme. When it was fully exposed, it ended up being just a strike tactic and people saw that this was jeopardizing an important service. To the extent the Town was willing to subordinate itself to that strategy, it lost the confidence of the public.

That same day bargaining resumed. There seemed to be some positive movement, though both sides were cautious. The Town "conceptually" accepted the idea of captains in the bargaining unit that day and issues of benefits and wages were discussed. The Town staff returned for a long, closed door meeting with the Town council that night.

Ridin' the roller coaster

The next day might be the fire fighters' last in jail. Negotiations resumed and the union representatives entered the meeting with a smile. The mood quickly darkened when Miles denied the previous day's "conceptual agreement" to the captains' inclusion. The union team was furious. Lass taunted Miles and the Town's attorney gathered his papers and left the room. The Town returned to its "final offer" of April 14. All the previous progress was gone. Berry broke the agreed upon press silence, accusing the Town of "psychological warfare tactics. They lift you up and then crash you down again. I thought this could be settled today, but it looks like it's going to go on. All this bitterness and rancor could be over, but it looks like it's going to go on." The fire fighters concluded this would be the last negotiation for a long time and prepared themselves mentally for a much longer battle.

With release imminent, the Town Council asked for a private meeting with the fire fighters again. The union refused until the Town also agreed the four jailed union negotiators could attend also. Preparing to transport the jailed fire fighters to station 1 for the meeting, McLean County's volatile sheriff, John King, arrested a CBS news camera man for trespassing on the driveway of the courthouse. The fire fighters were transported to the fire station to meet with the Council, but were shocked when their four negotiating team members, Lawson, Watson, Hanover and Kerber, were led out of the room to the apparatus floor. The remaining fire fighters met inconclusively with the Town Council. The union membership's willingness to continue the meeting angered the negotiating team.

When they returned to jail at 11 p.m., a few supporters and Lass approached the van. Sheriff King threatened to arrest the group. Even Lass meekly backed off. The fire fighters were not searched nor their cells locked. At 1 a.m. King and his deputies began to give them their belongings and they were released in small groups. No big public event would mark the end of their jail sentence. Awakened from their sleep, Lass, Berry and McAtee ferried them to the Falcon where their families joined them and a spontaneous party erupted.

Thursday, May 11 was a day-off. Bloomington fire fighters walked the picket lines while Normal's strikers enjoyed a day with their families. Don Bevers' wife Linda, due with a child during the first week of jailing, finally gave birth to a son, the blessed event mentioned by Walter Cronkite that evening on CBS News -- Normal's struggle was a nightly staple on the national news.

Friday the picket line resumed and Normal officials talked of their contract with Eagle 9-11. Monday's firing deadline was the next battle line. The fire fighters entered the station houses, cleaning out their personal property. In station 1 they found their union charter in the trash can, torn and with its frame broken.

That night the fire fighters met together formally, as a union, for the first time since the jailing. Ron Lawson asked the group, should they continue the strike? If only five or six more capitulated, the strike would be lost. If they were going to end it they should do it together. Was a secret ballot vote necessary? The fire fighters laughed; they ran down their roll call and unanimously, and sometimes humorously, affirmed their continued stance.

As the meeting broke up that warm spring night some of the fire fighters returned to picket duty at station one. A strange sight awaited them. Inside the station, spending the night, was Mayor Godfrey, Council members Bell and Maulson, Miles, Anderson and Assistant Manager Steve Westerdahl. They had a captive audience of one -- Jim Schrepfer. Schrepfer was a new probationary fire fighter, called to duty by the Town. He desperately wanted the job but didn't want to cross the union. He was given a picket pass for 56 hours, one week's work. He spent some time with the strikers, alone with the Chief and the Assistant Chief, and now, as the hours on the pass dwindled, with the Town Council and staff.

In some ways it was a comic night. The probationary fire fighter played cards with the Town staff, who eyed him warily and tried to convince him to stay. On the apparatus room floor Mayor Godfrey was trying out buttons on the ambulance, sounding the siren and flashing the lights, while Councilwoman Bell climbed on the hook and ladder. The footsteps on the roof that spring night weren't Santa Claus, but Lass spying. Earlier he had been at the window with some student supporters and other fire fighters, making faces at the Council members.

The next morning the crowd at the station was even bigger. Town staff emerged and tried to talk to individual fire fighters but were rebuffed, told to talk to the negotiating team. Would Schrepfer emerge and join the strike or stay in with the Town? The probationary fire fighter emerged, repeating some arguments the Town Council had given him the night before. Lass was soon in his face, cajoling and chiding him. Some of the fire fighters led Lass away and others talked with Schrepfer. He went back into the station and emerged a few minutes later, carrying his gear. The strike was one man stronger that morning and the Town had played and lost another card.

Claiming the job

Berry said the picket pass to Schrepfer, reminiscent of the pass to Lockport fire fighters used in Joliet, was a tactical move, a reminder that the union still controlled the Town's labor force:

This was part of our controlling the job. Even before Eagle 9-11, we were aware they were going to try and hire people. So Mike and the union members went and talked to them and organized them while they were on the list. As they were called in Mike made them sign, gave them picket line passes to cross the line to get hired. Jim Schrepfer was called to work and he used his picket line pass to cross the line and get hired. He spent the whole day and night in the fire station. The Town Council members were there, holding his hand. We were picketing outside. The next morning Mike revoked his picket line pass and tells him to come out. He did -- that deflated the city. They hired a new fire fighter and now the union has another striker. So then we had a negotiating session and with the combination of all of those things, this time they came to settle.

That Saturday was graduation at Illinois State University. Another crowd, 600 strong, gathered at Bloomington's Machinist Lodge 1000 hall to support the strikers. Donations and support came from union locals, particularly from public employees, from throughout Illinois. Lawson was in tears as he thanked those present for their support, vowing to continue to the bitter end.

Negotiations began again that afternoon. Buoyed by the rally, the union team was feeling confident and strolled into the session late. In the previous few days they felt they had added a new card to their hand. If the Town brought up Eagle 9-11 again, the fire fighters said they would bid for services as Local 2442 Inc. Negotiations went nowhere that afternoon, but the Town didn't just lay their final offer on the table and walk out. Negotiations were rescheduled for the next afternoon.

Offering to contract fire services, as a union, was a tactical move that resonated with the fire fighters, another sign that they would ultimately control the work. Berry remembers the idea germinating as the strike ended and options for the strikers looked bleak:

Once we got out of jail, we weren't sure where we would go. If the pressure of all the national publicity had not moved them to settle after 42 days, what do we do now? What are we going to do, picket? That's not going to have any impact. In the conversation Eagle 9-11 came up and somebody mentioned, They appropriated sixty or seventy thousand dollars for that.' I said, You know, there's seventy thousand dollars there, why don't we go and find out the bidding procedures? They passed this ordinance, they're going to provide the money. We could bid to provide fire protection for seventy thousand. That would sustain us for a while.' I thought of it initially as a kind of public relations move, but as we got to talking, the fire fighters said, We can do that.' It started picking up their spirits, that they could be the fire department. The whole idea re-inflated their confidence. So Mike and I went over to the Town Hall, made a big deal out of it, and asked for the bidding procedures.

We weren't getting anywhere in negotiations, they weren't moving. I called a caucus and said, What do you think about making this bid to do the work as a formal proposal?' The team said, Let's do it.' We got back to the table and presented the proposal to the Town as two options: Option A was a fair contract. I explained this was our preferred option but if the Town could not accept it, we did not want to work for the Town -- we would have a divorce. But if that happened we would both have a problem. The union would have a membership of highly trained fire fighters with no jobs. The Town would have no fire protection and would lose its investment in the fire fighters. So Option B is the union would agree to accept the contract that the Town had awarded to Eagle 9-11. The fire fighters would have jobs and the Town would have fire protection. After the contract expired and the Town could the renegotiate a more long term contract for services.

I remember Dave Anderson just kicked himself away from the table. You can't do that.' Sure we can, you just fired us. We need a job, you need fire fighters. You have the money, we'll do it.' That just blew them away. That proposal convinced them the strike wasn't over. This was a whole new scenario around which the whole dispute would continue and they would still be under public scrutiny.

The headline in the Pantagraph that day read, "Town Could Fire Fighters, Hire Union."

Winning a contract

The next afternoon the union's bargaining team took the lead, using Lass and Berry as sideline consultants. The union organizer and the attorney consciously stepped back from the bargaining table. Slowly the Town capitulated on a number of major points. The salient point, captains, was settled in the same way state mediator Ed Schultz had proposed six weeks previous and the fire fighters had recently re-offered. The captains would be in the unit but under a no-strike clause, their performance secured by a posted surety bond. At 2 a.m. all issues were settled and by 5 a.m., Monday, May 15, a skeleton crew of strikers was back in the station. Lieutenant Gary Trent, fire fighters Rick Mills, Mike Leisner and Don Bevers walked back into station number 1. There were no crowds outside the door, no TV cameras, just Pyro the dalmatian, tail-wagging, happy to have them back again.

Room 47 of the Falcon Motel became an all-day party, with laughter, jokes, tears and quiet conversations in the corners and around the parking lot. The strike that the fire fighters weren't supposed to win would be their victory, pulled from the proverbial fire more than once. At 5 p.m. two fire rigs pulled into the motel parking lot, bringing the on-duty fire fighters from the two stations. Group photos were posed for around the trucks and then a roll-call vote followed. Local 2442 had ratified the contract. The fire fighters and their families clambered onto the bright red trucks and rode them to the Town Hall for the Council meeting that Monday night.

As the Town Council meeting began, union spirits dropped when some of the Council members began questioning the contract. Was this another roller-coaster ride, another stop in the psychological warfare Berry warned them about? Mayor Godfrey asked if the union had accepted the contract and Lawson stepped forward, declaring that it had, 22-0. The council was polled, the tally was 5-2 for the contract, with Vernon Maulson and Paul Mattingly voting no. The Council's vote let loose a round of cheers, yells and tears from the fire fighters. Mayor Godfrey read from a prepared statement, saying:

Everyone involved has been a loser' and saying the strike's conclusion brings to a close perhaps the most traumatic moment in the history of community. ...It would be nothing short of hypocrisy for me to say that the processes which led to this agreement carry with them any semblance of a positive nature for the firemen, the citizens of this community or the members of the Town Council. ...The damage to the personal lives of those on both sides in this dispute will leave invisible scars that will be long in healing.'

With a very stern face, Lawson came forward to sign the agreement, noting, "I just hope that two years from now, we don't have to go through what we went through here."

The celebration didn't end at the Town Hall. The union members and their supporters gathered outside station one. With Ron Lawson holding the new contract, Ken Kerfoot with a giant 24/42 poster and Bill Kerber a new union charter, members of Fire Fighters 2442 officially "re-occupied" the fire house. They approached the building in hushed tones, then screaming and yelling once they were inside the door. They were like a returning army, reclaiming their homeland. Normal, Illinois had its first-ever public employee union and they had a contract.

Speeches were given and Mike Lass calmed the crowd into hushed tones, when he pulled a tattered piece of paper from his pocket, reading a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. that expressed the emotional depth of the past 56 days:

We will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. We will not hate you, but we cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws. We will soon wear you down by our capacity to suffer. And in winning our freedom, we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process.

Retrospective

What won this contract in a small, white-collar community? Lawson credited the fire fighters and their families sticking together, along with support from "all the other unions. Without them being here every day it would have been a lost cause."

Lass saw a combination of factors, saying it came down to:

A simple issue of rights and just the force of will. They (the Town) ended up with 42 days in jail to try and break the fire fighters. They brought in replacement workers. That was the maximum attempt to walk and starve. Walk and starve, go out and hire new people, and when that didn't work, they went for the contempt, put them in jail. All the classic antiwar tactics you could use to organize a community we put to play there. That all made the environment that allowed the firemen to come out after 42 days in jail and make a decision to go back to work or pick up the picket signs. They (the Town) threw in the sponge, they finally said, That's it. We can't.' 56 days. A lot of roller-coaster riding, the roller coaster ride of all roller coaster rides.

Berry noted two important developments: effective public relations to make the strike a national story and making Seyfarth, Shaw's presence an issue:

We didn't win because we had the power to win, we had to do a little bit of finessing. Nobody knew we were on strike, Normal was out of the news and we wanted to be in the news. Halfway through the strike, the Chicago Tribune got wind of it and had an interview with Ron Lawson in jail and played that up as a big story. That was breaking out of the local market into the national market. News coverage put the Town's tactics under public scrutiny and ultimately put pressure on the Town Council to settle.

Seyfarth, Shaw always attacked Mike Lass and then me, we were the outside agitators, we were starting the strikes, when in fact, they were. So we started making them the issue. It was their strike, they were manipulating the Town. I was developing that issue and it started getting some national coverage. That's where the wives came in. We didn't have any people on strike to do the work, they were all in jail. So it really came to the women, the wives had to carry the outside support.

Berry, like Lass, credited the wider community involvement as critical to sustaining the small group of fire fighters:

The students were very important in that strike. And this was really a total community effort. This one couldn't have been done without involving everybody, students, the community. This was much more Mike's, like an antiwar organizing where we're activating everybody. The other ones, seven, eight day strikes, you're basically dealing with it as a labor matter. But when it's fifty-six days they had to develop a political movement. Other labor unions had to be involved. There was a key point there right toward the end. The Trades & Labor Council, they didn't come to undercut us, they supported us. They actually were going to take their money out and boycott local banks. All that had an impact. It took that to overcome the strong psychological commitment that the Town had to beat us. When we had that guerilla theater, that was also very important, because there was a point where they wanted us to become violent and there were people that might have done it. They were getting very frustrated and very angry. And that whole guerilla thing with the students converted that anger into ridicule. That was a much better tactic that defused the hostility that was developing. It was all part of being a mass movement, as opposed to just strictly a strike and a labor dispute.

I think Normal was a strategic strike where we beat them when they should have beat us. They had everything going for them and they still didn't beat us. It was a big enough issue that a lot of people realized there had to be a better way to resolve a labor dispute. And the next one was Aurora. There was another one where they should have beat us and they almost did too. And then Chicago. Those three, each one was a stepping stone. Those are the ones that had statewide impact.

Normal helped boost publicity and commitment to a statewide collective bargaining bill. If strikes like this continued to garner national media attention, it spurred cries for political change. Much of the publicity was ridicule, mocking the town's name of Normal. Some was sympathetic to the fire fighters, Time magazine featuring a cartoon of fire fighters tied up with a hose and guarded by a shotgun toting sheriff. The cartoon's caption: "Welcome to Normal."

|