|

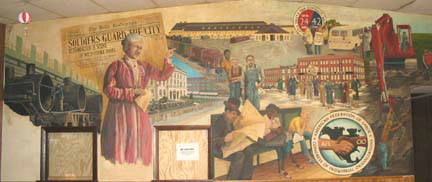

| National Guard machine gun emplacement, Bloomington C&A Shops, summer 1922 (McLean County Historical Society) |

|

Despite its post-war glow, the labor movement's optimism soon soured after the war. The Chicago Federation of Labor's ambitious plans to organize packinghouse and steel workers were defeated. The "American Plan" was formulated by business, promoting a non-union workplace. "We do not believe it to be the wish of the people of this country," a U.S. Steel official had said, "that a man's right to work shall be made dependent upon his membership in any organization (Brody, 107)." And a 1922 nationwide defeat of railroad shop workers crushed the AFL's largest contingent of industrial workers, a defeat that slowed local union efforts.

The railroads were the nation's largest industry. In 1917 the railroads operated on 360,000 miles of track and grossed four billion dollars. In 1920 2,236,000 workers served the industry, 400,000 of them shop workers. The nation's railroad repair shops were the nation's third largest manufacturer. Shop workers outnumbered meatpacking, iron and steel workers combined (Davis, 10-11).

The 1,800 shop employees of the Chicago & Alton Railroad were McLean County's largest industrial workforce. They had organized in the early 1900s and were the labor community's backbone. Most were white, a mixed group of German, English, Irish, Swedish and German-Hungarian background. African-Americans worked in the roundhouse and the scrap yard but were denied union membership. Most shop workers had skilled trades -- blacksmiths, machinists, boilermakers, sheet metal workers, painters, carmen and carpenters. Through apprenticeship these workers passed on their craft and skills to their sons and a new generation of workers. Besides the Trades & Labor Assembly, they had their own railroad shop coalition, Systems Federation 29 (AFL), which bargained with the C&A.

The Woodrow Wilson Administration meant positive changes for rail workers. The Adamson Act of 1916 gave operating railroaders -- engineers, firemen, trainmen and conductors -- the eight hour day. Wilson established the Department of Labor and his first appointee, mine worker William B. Wilson, pushed union organization and recognition. One of the new Labor Department's first interventions was in Bloomington in 1913, when the federal government mediated contract talks between the C&A and System Federation 29. The railroad had refused to recognize the shop workers' combined group. Wilson sent in his commissioner of conciliation, James Hogan. Hogan succeeded, giving the C&A's shopmen a contract, recognition of their federated agreement and a modest pay hike. The breakthrough locally led to similar contracts on three other railroads (Davis, 32-33).

Because of wartime traffic tie-ups and rail employees leaving for military services or higher wages in other industries, the federal government seized control of the railroads on January 4, 1918. President Wilson appointed his son-in-law, William G. McAdoo, as director general. One of his first actions was establishing a Railroad Wage Commission. He also issued General Order 8, which said there would be no discrimination in employment because of union membership. His wage board issued its findings in April 1918, calling for increased wages, but the mandate was scorned by workers because it was based on 1915 wage rates, not wartime wages. In response McAdoo formed the Railway Board of Adjustment, which set an eight hour day, time-and-a-half for overtime, and a 68 cent an hour wage rate for rail shop workers (ibid, 36-39).

The rail workers wartime gains quickly ended. Congress passed the Transportation Act in February 1920, establishing the Railroad Labor Board to handle grievances and problems. In July 1920 the Board gave the shop workers another 13 cents an hour. With Republican Warren Harding's election that November the Board shifted to management's favor. On June 1, 1921 the Board cut rail workers wages 12.5 percent. In August overtime pay for Sundays and holidays was cut and in October, a prohibition against piecework was rescinded. Rail workers set a strike deadline for November 1, 1921. Harding's administration made promises to the operating unions and the strike was called off (ibid, 53-57).

In May 1922 the Board announced wages would be cut another seven cents an hour on July 1. Taking a national vote, the shop unions decided to strike, but the operating crafts deferred. On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad shop workers "hit the bricks," including all 1,800 at Bloomington's C&A Shops.

In Bloomington the strike was calm until the C&A began importing strikebreakers. Local carpenters refused to build housing for the replacements and local citizens evaded deputizing by the sheriff (Knutson, 5). On July 6 the Sheriff telegraphed the Governor, asking for the National Guard, even though all was calm in the city (ibid, 6). On July 7 track maintenance workers walked out in sympathy.

The calm was broken that evening. After a baseball game near the shops, several hundred strikers marched through the complex, forcing foremen and clerks to leave. Some shots were fired, although no injuries were reported. The railroad demanded armed protection. On July 8 Mayor Edward Jones telegraphed the Governor, saying that "...destruction of life and property is imminent and will occur unless protection is afforded at once by state troops." On July 10 the National Guard was sent to Bloomington; an angry crowd of 200 met them at the station. Tents, field kitchens and machine gun emplacements were established around the shops complex. The city was declared under martial law and a local Judge, Louis FitzHenry, issued a temporary restraining order preventing "picketing of Bloomington shops by strikers, interference with the operation of trains, intimidation of employees and conspiracy (ibid, 8)."

On their first duty night the 400 militia members, which included a 65-member machine gun company, were confronted by an angry mob of 2000. The military patrols fixed bayonets to keep the crowd back. An intervening heavy thunderstorm dispersed the crowd, though later that night a few shots were fired at the soldiers, who returned 300 rounds in response. The next morning the first strikebreakers arrived (ibid, 9).

Railroad machinists and later president of Machinists 342 Joseph Dewey Penn remembered the National Guard and the union picket lines that faced it: We had to keep moving, the soldiers were there, they had their bayonets on. I'd never saw anybody in the militia that worked for a living; I suppose they all did, but they certainly didn't act like it (Matejka, 4).

The strikebreakers were not necessarily skilled workers but were often transients grabbing a quick buck. Many hopped from railroad to railroad, gathering sign-up bonuses. In August 1922 the nation's railroads had 91,000 fewer workers but paid out $2 million more in salaries. The strikebreakers were confined to company property for their own safety. The National Guard was no more popular -- in town barbers refused to cut their hair and women would not dance with them. The once serious incident occurred August 14 when a guardsman fired at a passing car, seriously injuring Mrs. Viola Ogan, a passenger in the vehicle (Knutson, 11-12).

Although the strikers were without pay, the railroads were without skilled mechanics for their maintenance-intensive steam locomotives. From August through September 1922, 71 percent of the nation's locomotives failed their monthly inspection. Rank and file members of the operating brotherhoods were restless and sporadic sympathy strikes were breaking out, totally shutting down some railroads. A national court injunction broke the strike's backbone. President Warren Harding made a faint hearted effort to negotiate and involved Secretary of Commerce Hebert Hoover and Labor Secretary John Davis in mediation, which both took seriously. By the end of August Attorney General Harry Daughtery, who was militantly anti-union, convinced Harding national action was needed. On September 1 newly appointed federal judge James H. Wilkerson of the U.S. District Court in Illinois handed down one of the "most sweeping federal injunctions in U.S. history (Davis, 131)." The injunction outlawed picketing, "loitering and congregating" near railroad facilities, communication about the strike between workers or from their union and the use of union funds to support strike activities (ibid., 130-131).

Despite some desertions and their national organizations hampered by the injunction, Bloomington's shopmen held on, marching en masse around the complex on September 18. On September 24 local negotiations began with President Bierd of the C&A, the Association of Commerce, the mayor and ten union representatives. Union members voted to reject Bierd's first proposal. With no movement the McLean County Farm Bureau intervened, asking that Bierd be called before a judge to explain his objections to settlement. This created small movement and on October 3 the shopmen voted to return to work, accepting a lower wage, but 2-4 cents higher than the July 1 order, forfeiting seniority rights to the strikebreakers and joining a company union (Knutson, 18-19).

With their unions broken, a hatred and bitterness lingered after the strike. C&A machinist Thorton Belz ruefully remembers returning to work and finding a message from the strikebreakers scrawled in chalk on a locomotive smokebox, "We got the dollars, now you can have the cents." He later saw a replacement worker injured by a drilling machine and no one went to his assistance (Matejka & Koos, 150). Nellie Daly remembered her brother's childhood friend who crossed the picket line and went back to work. "He went in and my brother never had any use for him after that. He did everything under the sun to get back in my brother's good graces but he never made it. It was terrible to be a scab (ibid, 36)."

Federal intervention to defeat the shopworkers' strike slowed union activity throughout the 1920s. Nationally most unions lost members in the decade and business trumpeted the "American Plan," which was basically maintaining a non-union status.

The brave and tragic fight of the shopmen and their supporters represented the last great upsurge of industrial unionism until the 1930s. Throughout the 1920s the labor movement was dominated by small conservative craft unions. ...Just like the steelworkers and the coal miners, the shopmen also endured federal suppression during the postwar period. What set the shopmen apart from other industrial workers, though, was that the state dealt the death blow to their hopes of national protection and relative security (Davis, 172).

Another economic consequence of the strike was the C&A's $14 million bankruptcy. The strike did not directly cause the railroad's failure. The C&A had been an innovative, financially prosperous property throughout the 19th century. The Harriman syndicate, which controlled numerous railroads in the early 1900s, gained control of the C&A in 1899. They owned the line for seven years and through stock manipulation made $23 million from it, saddling the company with long-term debt. Slow recovery after World War I, coal strikes and the shop strike all exposed the company's weakness and forced it into receivership. Its future now lay with other companies and controllers (Knutson, 4, 14). The shopworkers maintained their unions and regained contracts with the C&A by the late 1920s. However, few new unions were organized in the community until the 1930s.

Although the shopworkers strike in 1922 and the 1919 Labor Party were defeated, union members gained political power in 1923 -- as Republicans.

Throwing off the commission form of government and returning to the ward system, Bloomington voters in 1923 chose between a traditional slate of Democrats and Republicans -- but many of the Republicans, including the mayoral candidate, were trade unionists.

The slate was led by railroad engineer Frank E. Shorthose. There was nothing politically radical about his platform, which included support for law enforcement, establishing a health department, building a viaduct over the rail lines on South Main Street, and maintaining parks, the fire department and the water system.

Interestingly, the weekend before the election that 67-year-old Socialist warhorse and former Presidential candidate, Eugene V. Debs, spoke at the Coliseum on "The New Social Order," addressing issues of poverty and peace. Debs made no mention of the local election ("Debs," 5).

On April 3 Shorthose defeated Democrat Emerson J. Gilmore by a 3-1 margin. Two rail workers, Frank Donovan and Richard Barry, running as independents, were the only non-Republicans elected. The new city council included union members Mayor Shorthose; Val Simhauser, a service station operator and an active member of the C&A Shops' Machinists; John Larson, a sheet metal worker and a union contractor; C.H. Kurtz, a railroad freight agent; Frank Donovan, a C&A pipefitter; Richard Barry, a C&A fireman; Ralph Greene, a Pantagraph typographer; and, Charles H. Lawyer, a barber. The remaining five alderman were predominately from small business, including a farmer ("Who is Who," 5).

Labor's political reign was short-lived, as Mayor Shorthouse died of cirrhosis of the liver on January 4, 1924. Shorthose was eulogized with a public ceremony at the Bloomington Consistory, with full honors from the Masons and the BLE. The Association of Commerce urged businesses to close and children were taken from schools to file by the casket. The Pantagraph editorialized on his unrealized potential and noted that "Mayor Shorthose is mourned as a veteran among the railroad employes of the city, where he pursed his occupation much the same as hundreds of others have done, with faithfulness and integrity (Mayor Shorthose, 4)."

Shorthose was succeeded by council member Frank H. Blose, one of the city's few remaining blacksmiths. In the 1930s P.J. Irvin, president of the Mine Workers local, served on the city council.

|