|

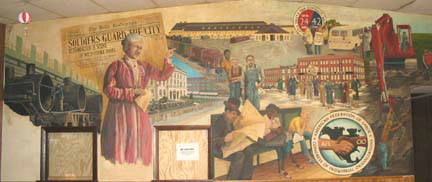

| Illinois National Guard troops with a machine gun emplacement, Bloomington Chicago & Alton Railroad Shops, summer 1922. Photo credit: McLean County Museum of History |

|

The term “union busting” was not used in 1922, but an epic national railroad strike that year brought deaths, beatings, broke union contracts and an incredibly repressive Chicago court injunction.

Across Illinois thousands worked “backstage” for the steam railroads – machinists, boilermakers, sheet metal workers, railway carmen – nursing the labor intensive steam locomotive and building and rebuilding rail cars.

During President Woodrow Wilson’s Administration (1915-1921), railroad workers gained union recognition along with improved wages and conditions. During World War I, the U.S. railroads were nationalized.

When Republican President Warren Harding’s Administration (1921-1923) came to power, the railroads returned to private ownership and the federal Railway Labor Board was stacked with Republican appointees, who mandated wage cuts and eliminated overtime pay.

On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad shop workers struck. Before airlines and interstates, if railroads were not running, the economy came to a standstill. The operating crafts – engineers, conductors, firemen, trainmen – continued to work but no maintenance quickly halted railroad traffic. Plus a national coal strike was also happening.

By July 10 railroads were ordering workers to return or lose their seniority. By July 20 numerous court injunctions were issued limiting union activity. Strikebreakers and company guards were recruited and in August 1922 the nation’s railroads paid out $2 million more in salaries, even though their workforce was on the streets. Equipment failures abounded and by September 1, 71 percent of all locomotives failed their monthly inspection.

Chicago and East St. Louis were the nation’s rail hubs and contained multiple facilities. Every junction or smaller city had a locomotive roundhouse or some repair facilities. Major railroad system repair shops with over 1,000 workers were located in Aurora, Bloomington, Centralia, Danville, Decatur, Galesburg, Joliet and Silvis (Rock Island).

Company guards and militia units were dispatched. Once troops arrived, companies built dormitories or housed strikebreakers in rail cars. Many were “floaters” with no experience, roaming from railroad to railroad to collect a bonus. Companies used these workers to present a modicum of activity. Despite almost 300 strikebreakers housed on Wabash Railroad property, the Decatur Herald reported on August 31 that the shops were “quiet as a holiday. … Entering the locomotive shop, one sees a long line of locomotives, that have not been

touched and another line of engines stripped of all fittings, standing there in the same condition in which the men left them two months ago.” In many communities local law enforcement was strike sympathetic and enforced laws against strikebreakers.

A 12-year-old Clinton boy was the nation’s first strike fatality. James Fitzgerald and his son were observing Illinois Central railroad guards escorting strikebreakers into town. A crowd gathered and the guards opened fire, shooting young James through the lungs, his father through both legs. On July 11, every store in Clinton closed as thousands attended the youth’s funeral. Company guards were charged but none were convicted.

Violence continued; company guards and militia units fired at strikers. Strikers attacked strikebreakers and beat them. A common tactic was to kidnap strike breakers, beat them, steal their clothing and leave them in a cornfield with a threat never to return.

By August the unions were ready to settle. President Harding dispatched Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover to mediate. The unions were receptive but management refused.

In a Chicago courtroom on September 1 a sweeping court injunction throttled the strike. Federal judge James Wilkerson, pushed by U.S. Attorney General Harry Daughtery, let loose a court order that outlawed picketing, "loitering and congregating" near railroad facilities, communication about the strike between workers or from their union and the use of union funds to support strike activities.

AFL President Samuel Gompers, who urged unions to defy the court order, quipped that if workers couldn’t call strikebreakers scabs, perhaps they could use the term “industrial angels.”

The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s President Daniel Willard negotiated a work return recognizing seniority rights that 14 railroads accepted. The remainder held out, running their shops with strikebreakers or desperate union members who returned.

The strike was broken and the 1920s business promoted “American Plan” triumphed – no unions. Mass organizing was thwarted for another decade. Under the 1926 Railway Labor Act, workers won organizing rights, but the conditions lost took years to rebuild. Certain railroad executives were bound to destroy unions and the shop crafts were their victim.

- Mike Matejka

|